As a Tóibín fan it was like coming home to a cosy room as I settled in to page one and his simple very clear narrator’s voice with its always formal tone elicited by mainly short sentences with no contractions. It’s been twenty years or so of novelistic time since the happy ending of his novel Brooklyn (2009) when Eilis Lacey, from Enniscorthy (Tóibín’s home town in County Wexford, NE Ireland) returned to Brooklyn to continue her role as the recent wife of Italian, Tony Fiorello and to raise a family on Long Island.

Tóibín wastes no time and opens the narrative with the plot point that propels the story: a stranger arrives at Eilis’s front door with a piece of harsh news and his even harsher promise to make things worse. She lives in an enclave of the Fiorello family including her parents-in-law and Tony’s married brothers and she has forged a place in that family that she thought was secure but it’s her reaction to the news, and the only action she feels she can take, that causes her to doubt everything she has done in the past. This is despite her in-laws offering to solve the problem for her. Her stubborn Irish decision is played against the Italian pragmatic approach which she finds untenable. She refuses their help.

This is a common novelistic format: begin with an explosive event and then fill in the backstory along with the repercussions of the bomb. The reader is hooked from page one.

Brooklyn is an immigrant tale and the choices an immigrant must make, personified in the story as two men, one Irish and one an immigrant, like herself, forging an American life. She returns to Ireland to find if she has made the right choice; a little foolhardy since she has already married the Italian-American, something she does not tell anyone including her mother. She returns to America, her choice forced upon her because of her previous decisions. So, there has always been a doubt lurking in the dark, in the back of her mind and this doubt is brought to the fore in this new novel of a much older Eilis Lacey, a married American, secure, and with two teenage children.

She returns again to Ireland on the pretext of her mother’s forthcoming 80th birthday. Her twenty year ago Irish lover is still unmarried, but plans are underway to fix that. Can the way forward get more bumpy? Yes. Her children arrive! How does Eilis navigate her return to the family and ‘her Irish home’? She makes mistakes but will she learn from them? Meanwhile Tony, her foolish but devastated husband waits longingly for her to return to ‘her American home’. Once an immigrant, always an immigrant?

This is literary family fiction at its best.

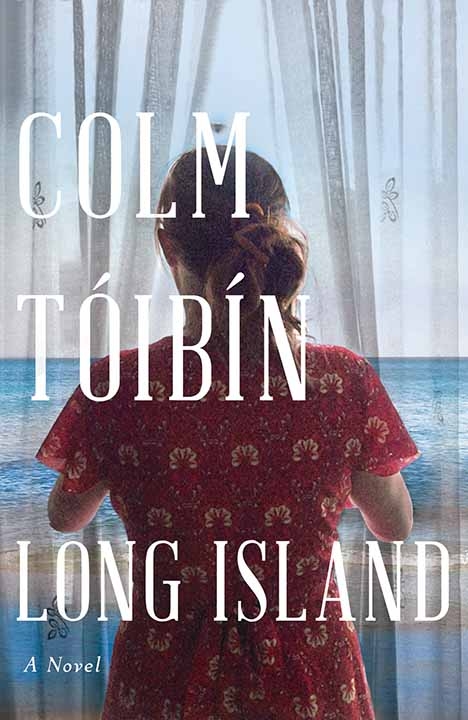

You can buy the book here, in various formats.

On YouTube there are several videos, short and long, of Tóibín talking about this new book. Start with this short one.