If you are bored rigid by style guides, grammar tomes, and ‘How to write’ books, skip this one. However if you are fascinated by the building blocks of a sentence; how English has changed; and the black, white, and beige of grammar rules then keep reading.

Steven Pinker, the American “Rock Star” psychologist and a Professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard University conducts research on language and cognition and has penned many popular and accessible books on language, the mind, and thought. His latest book is this one which came out in 2014 and for which he received the International Award of the Plain English Campaign.

Generally commentators on the English language fall into two broad camps: the prescriptivists, those who believe there are rules that define how language should be used, and that mistakes result from breaking those rules; and the descriptivists, those who believe that a language is defined by what people do with it. You may recognise the former as “sticklers, pedants, peevers, snobs, snoots, nit-pickers, traditionalists, language police, usage nannies, grammar Nazis, and the Gotcha! Gang” but Pinker also damns the latter as “hypocrites: they adhere to standards of correct usage in their own writing but discourage the teaching and dissemination of those standards to others, thereby denying the possibility of social advancement to the less privileged.”

Pinker is the chair of the Usage Panel of the famously prescriptive American Heritage Dictionary but he quotes the editor as saying, “We pay attention to the way people use the language”, a clearly descriptive view. Pinker, like most writers and readers, sit on the fence. Their anchor? Clarity and meaning. There are words that we continuously mis-use, such as decimate to mean ‘destroy most of’ instead of ‘destroy a tenth of’. There is no point in using the word in its original meaning if the reader or listener believes it to mean something else. The old prescriptivist rule of ‘never split an infinitive’ only exists because of the early English need to squeeze the language to fit Latin rules. The Latin word for the English verb to go is a single word ire; it’s impossible to split a single word but splitting the English word is of course possible: ‘to boldly go where no man has gone before’ is fine by Steven Pinker, and most people, I suspect.

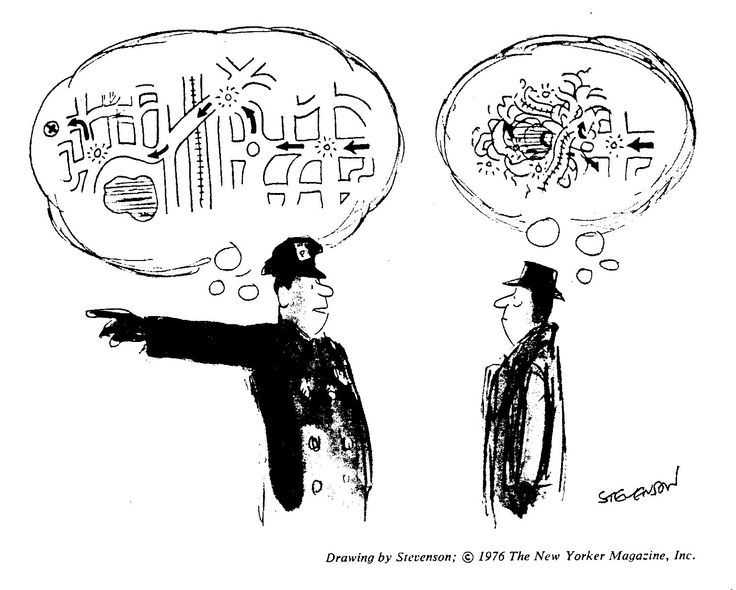

His chapter 3, The Curse of Knowledge, is a delight and has cleared up that old annoyance illustrated in the following cartoon

“The curse of knowledge: a difficulty in imagining what it is like for someone else not to know something that you know.” When someone gives you inadequate (to you) directions that they think are obvious (to them) and ends with the phrase ‘you can’t miss it’, you usually will. See! It’s their fault, not yours.

And did you notice I used the plural pronoun they for a singular subject someone? This has been common usage for over a century and solves the English language’s lack of a neutral singular pronoun. Oh, and did you notice I began that sentence with the conjunction, and? This was something that was considered the grammatical sin of sins in the 60s and 70s but has again been used for centuries.

However the last, and longest chapter Telling Right from Wrong will give you a lot of joy, understanding, and the edge in arguments about where to put that comma, when to use lay and lie, and the sometimes acceptable use of an adjective when the grammar police insist on an adverb.

P.S. In a student exam paper, recently, there appeared a sentence that confused everyone. “It would be a great idea if we went to the park tomorrow.” This is a sentence about the future but with the modal verb would, and the auxiliary past tense verb went. Using the future form sounds strange: “It will be a great idea if we will go to the park tomorrow.” No, the past tense is correct. This is called factual remoteness as Pinker explains with the example, If you left now, you would get there on time. “The if-clause contains a verb which sets up a hypothetical world; the then-clause explores what will happen in that world, using a modal auxiliary. Both clauses use the past tense to express the meaning ‘factual remoteness’.”

Note the full stop after the quote (not ‘ ….remoteness.’”). You’ll have to read the book now to find out what Pinker says about this (or is it that?).

You can by the kindle edition, and paper editions, here.