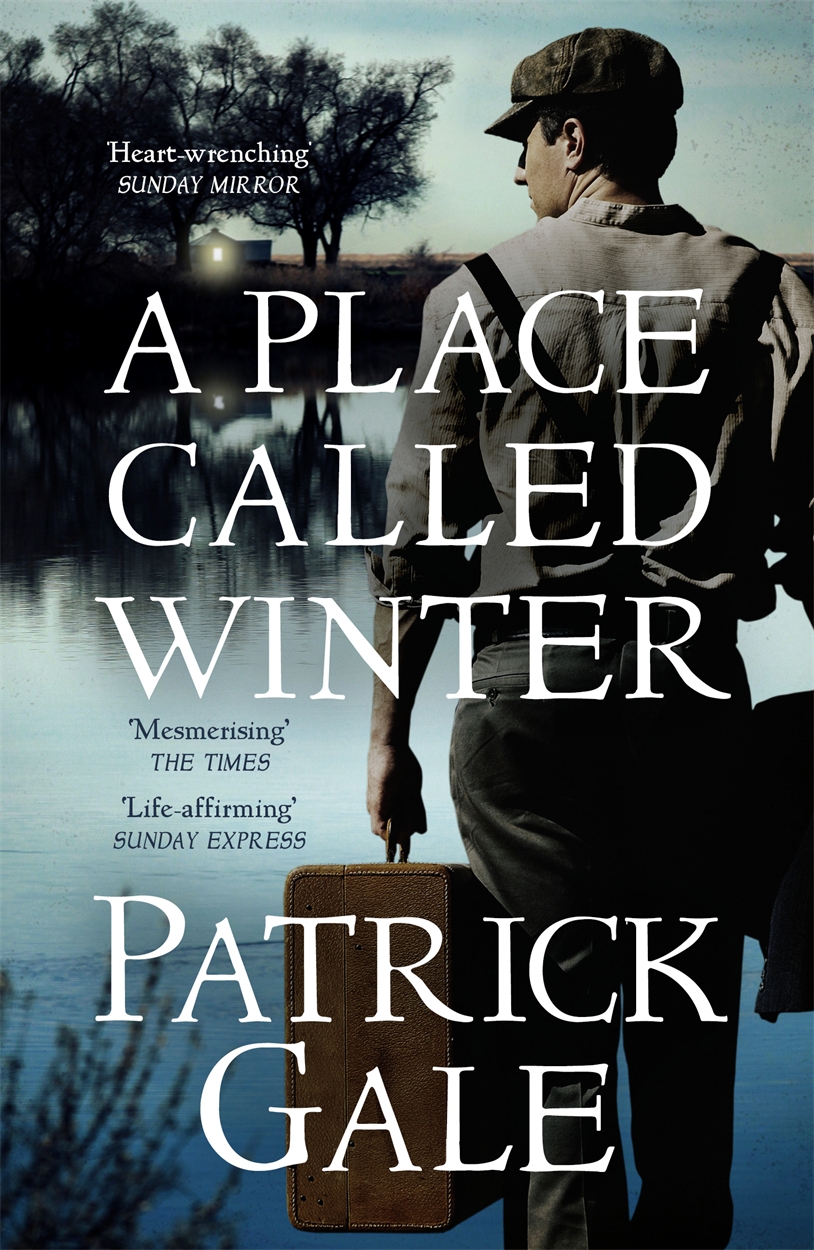

Author, Author by David Lodge

When the Irish writer, Colm Tóibín, was working on his (masterpiece?) The Master (2004), about the American-English writer Henry James, he visited Lamb House, HJ’s East Sussex home in the town of Rye, and met 3 other writers all doing exactly what he was doing: researching HJ. There has been a resurgence in interest in Henry James usually considered an obtuse fiction writer but a recognition that his most alluring characteristic is that he was, like most literary greats, a writer like no other. The English writer, David Lodge, also produced a book on HJ in 2004 which seemed to have sunk from view since Tóibín’s effort was so successful: it was shortlisted for the Booker-Man Prize in 2004. Lodge’s story focuses on the same events, and in particular James’s unsuccessful foray into the theatre, as Tóibín’s, but it is a very different novel.

Lodges’s story is more old-fashioned in the sense that he puts HJ in the midst of his history setting up a life of work, friendships, and his exhausting social life, into which then Lodge plunges the unsuspecting, and dare I say it, theatrically naive writer to surround the reader with an understanding of the great cataclysm that befell HJ and his subsequent inability to come to terms with what had happened: failure.

It is not enough that one succeeds – others must fail.

However, Lodge has a more nuanced ambition: the juxtaposition of a literary figure and his sense of his own talent against the success of his peers, and in HJ’s terms, his inferiors. James had a contemptuous attitude towards his contemporary, Oscar Wilde, whose unprecedented theatrical success was a claw in his side, made more painful by the success of An Ideal Husband, an early performance James attended on the opening night of his own fateful play Guy Domville. He hurried from the thunderous and appreciative applause of Wilde’s audience to the jeering ‘gods’ of his own. HJ was deeply humiliated by the audience’s reaction to his play. Guy Domville only lasted three weeks and was, ironicly, replaced by Wilde’s even-bigger success, The Importance of Being Earnest. Wilde’s subsequent fall, social disgrace, trial for sodomy, and imprisonment were his just desserts in James’s mind even if they were, not for low-brow literary frippery, but for ‘outrageous and disgraceful conduct’; James’s own sexual proclivities were always buried deep and, it is surmised, never allowed expression. However it was the popular successes of his good friends, George Du Maurier and Constance Fenimore Woolson that really contrasted HJ’s failure and showed his idea of friendship to be constantly compromised.

It was Wilde who quipped

Anyone can sympathise with a friend’s success, but it takes a truly exceptional nature to rejoice in a friend’s failure;

which he topped a little time later with,

It is not enough that one succeeds – others must fail.

Gore Vidal, that Wilde-ish American, rephrased it in the late twentieth century as

Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something inside me dies.

HJ’s close friend, George Du Maurier, was famous as an illustrator for Punch magazine and only turned to writing a novel, Trilby, because of failing eyesight: he dictated the text to his wife. Trilby was, by today’s jargon, a blockbuster, on both sides of the Atlantic, in print and on stage; a level of success that Du Maurier never quite understood. Neither did HJ. The Trilby hat, the phrase ‘in the altogether’ and the name ‘Svengali’ are all due to George Du Maurier, who is now forgotten; his name only lives on in that of his grand-daughter, the novelist Daphne Du Maurier (1907 – 1989), author of Rebecca and Don’t Look Now.

Henry James had many female friends but his closest was Constance Fenimore Woolson (grand-niece of James Fenimore Cooper). She, as did Du Maurier, considered HJ as a writer of the highest order and was always self-deprecating about her own short stories and novels which sold much better than HJ’s; he agreed with her but never said so. He was always haunted by her suicide – she fell from her apartment window in Venice to the payment below – in the fear that it had something to do with her un-reciprocated love for him.

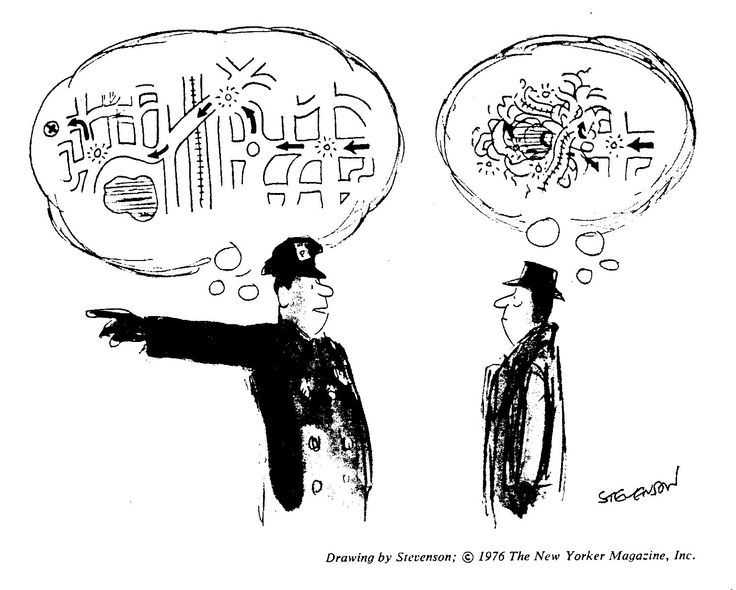

In both Tóibín’s and Lodge’s accounts the failure, and in particular the doomed opening night, of Guy Domville is the focus, although Tóibín places it near the beginning, while Lodge puts it near the end. Both also are deeply interested in HJ’s recovery and his return to prose-writing. However Lodge’s structure of the event wrings every bit of drama there is. He alternates the thoughts and utterances of the audience members– HJ’s friends and allies – on the opening night with James’s actions and thoughts as he dresses and prepares for the evening, sits through a performance of Wilde’s An Ideal Husband, – which he hates and thinks is crass and silly, and then hurries to St James Theatre to be on hand, if required, for the curtain-call. It’s a very effective use of dramatic irony – the reader knows what the protagonist doesn’t – and when George Alexander, having just taken his own curtain call, beckons the unsuspecting James onto the stage, HJ assumes it has all gone well (readers mentally yell, ‘No, James! No!’); but when his presence in the spot-light elicits a volley of abuse from the cheap-seats he is confused and to make matters worse bows not once but twice causing the rabble to ramp-up the volume of their displeasure. The already humiliating moment is compounded by Alexander who then makes a fawning and apologetic speech about him promising ‘to do better, next time.’ Despite mixed reviews – and positive ones from the youthful but the then unknown H.G Wells and George Bernard Shaw – no report, vocally or in print, avoided the mention of the reaction from the ‘gods’, and the play was doomed.

Whenever a friend succeeds, a little something inside me dies.

What Lodge is getting at is summed up thus,

Something had happened in the culture of the English-speaking world in the past few decades, some huge seismic shift caused by a number of different converging forces – the spread and thinning of literacy, the leveling effect of democracy, the rampart energy of capitalism, the distorting of values by journalism and advertising – which made it impossible for a practitioner of art of fiction to achieve both excellence and popularity, as Scott and Balzac, Dickens and George Elliot, has done in their prime.

And the result of this was a growing craving for un-intellectual entertainment. Lodge is referring to, of course, the difference between what today we call popular fiction and literary fiction.

The plot of Guy Domville angered the public the most: an eligible bachelor, a Catholic, plans to enter the priest-hood, but he is the last of his line; he discovers that he is loved, decides therefore to marry, then realises his intended is loved by another; he fosters that relationship, succeeds, and then joins the priesthood anyway. The End; three acts and over two hours to finish as it began, and no happy ending. To James it was a serious dilemma, skillfully presented as art, to the public it was boring.

The effect of such an event on a writer, his work, his sense of himself, and his friendships is what makes this novel so engaging. It’s one of the most enlightening works on success, failure, and friendship and any reader interested in such things should read it no matter what their artistic bent.

The review of Author, Author in The Independent in 2004 puts it succinctly;

Lodge deploys all his seductive storytelling craft to explore not merely the life and art of James himself, but the fate of any proud writer in an age of hype and spin.

David Lodge’s Author, Author is an immensely enjoyable work; I scheduled reading time – always a good sign.

The kindle and paper editions of Author, Author are available here.

I leave the last word to Henry James: We work in the dark – we do what we can – we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.