In this semi-autobiographical novel, a classic of American Modern Literature and set during the Depression at the University of Wisconsin, it isn’t surprising that the first person narrator, Larry Morgan, is a writer and so there are many references to the art, misuse, difficulties, and frustrations of such a profession.

Are writers reporters, prophets, crazies, entertainers, preachers, judges, what?

Is the gift, the talent, its own justification?

The process of writing fiction is an expression of self-discovery: being free and relaxed enough to let the sub-conscious out. And when it comes out you grab it and write it down. All the experiences of the world, the good, the bad, the insignificant, and the inferred make up one’s past life and the sub-conscious arranges them into memories which may or may not be accurate and can sometimes be perverse.

From these memories, the talent springs – the activity of imagining – but most of us, when the ‘talent springs’, do nothing about it. Scenes, conversations, ideas, rehearsed retorts, and wishful decisions occur to everyone all the time but only the writers write them down. But to write it down, you need to be practiced at writing things down, putting the products of your senses into words, and knowing the difference between a gerund and the infinitive.

Writing takes talent but it also takes practice. You can teach the practice but you can’t teach the talent.

Crossing to Safety (1987) tells the story of the remarkable friendship between Larry (the narrator) and Sally Morgan, young, poor, intelligent, and curious and a slightly older couple, Sid and Charity Lang, already ensconced in the English Department, and to the Morgans, a wonderfully urbane, astute, fascinating, devoted, and wealthy couple who take the newbies under their luxurious wings.

It’s easy for a first person narrator to slip into the third – they could tell a story, just like Terry Hayes does in I Am Pilgrim, – just as it is equally easy for the third person to get so close to a character that it a-l-m-o-s-t becomes the first. That’s why this more usual knack is sometimes called close writing. In more literary circles it’s called free indirect discourse. I prefer the less formal.

What is unusual here is that Larry, Stegner’s first-person narrator, has only just met Sid and Charity and knows nothing about how their past unfolded, nor do they tell him. This is not a problem for Stegner. He imagines the meeting and early courtship of Sid and Charity;

“Who is this boy?” I can imagine her mother asking. “Do we know him? Do we know his family?” Suppose they are sitting …”

Yes, an audacious technique but one that works given that imagining is what fiction writing is all about.

It’s also audacious to let a character, Charity’s sister, keep the name Comfort. It’s likely Stegner didn’t choose it; it just happened. Things like that often occur when writing fiction. I know of a novelist who, at 83,000 words, thought he had nothing but a pile of poo until out of the mouth of a young character came, out of the blue, the title of the thing. Not only did the phrase give the thing a name, and its theme, it also turned the pile of poo into a novel and out of relief and gratitude the author burst into tears.

It’s moments like these that one could easily believe that fiction comes unbidden, from another place, from another being: fate, a muse maybe, or even a spirit or god. It’s also the reason why you might hear young writers foolishly say, “Oh, actually it wrote itself.” That’s nonsense of course, but the feeling is real.

Being a semi-autobiographical novel, the events may be part of the writer’s past but the intimate moments, the conversations, and minute-by-minute thoughts must rely on imagination; imagined and written down.

The fulcrum of this quartet of characters is Charity Lang. She is forceful, controlling, opinionated, always right, passive aggressive, and never backs down. Two major scenes stick in my mind and will for some time to come. I can’t describe them as that would give too much away but the first revolves around preparation for a camping expedition and whether a packet of tea-bags was packed, or not. Seemingly a trite scenario but in the hands of Stegner it’s a pivotal moment in the building of Charity’s character. The second, the devastating climax, is about who should or shouldn’t go on a family picnic. Here the character of Charity is at its most prickly, unbending, and cruel. However, the reader understands her point of view, and it’s a tribute to Stegner that you also understand the three other points of view. It’s a shattering scene.

This is a book of rich language with a commitment to nature, happiness, and the human foibles that shatter or uplift our lives.

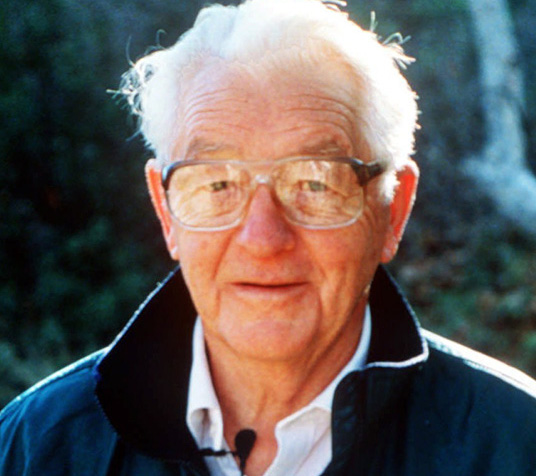

Here you can view an interview with Stegner from the early 1970s.

And here is an hour long documentary “Wallace Stegner: A Writer’s Life,” narrated by Robert Redford and produced only a few years before the writer’s death in 1993.

The book in various formats can be bought here.