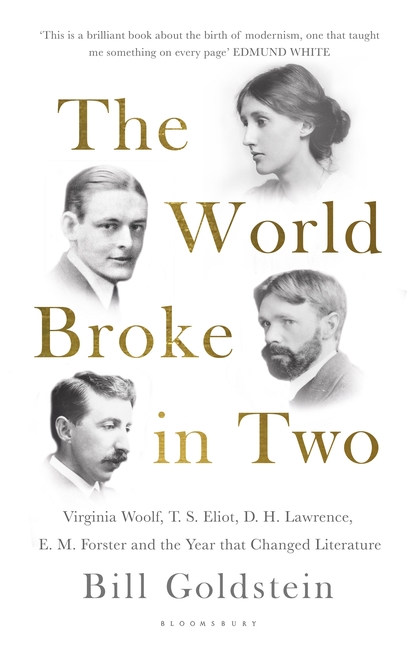

In 1922 the literary world buckled and, according to Goldstein, broke under the weight of four powerful novelists. This is an account of what happened.

In January 1922 Adeline Woolf, everyone called her Virginia, turned forty and was very sick with influenza which stopped her writing; T. S. Eliot, everyone called him Tom, 34, had been over worked, unhappy, in therapy, but now quietly confident since he had started writing again but fearful of returning to work in the Bank that trapped him between the concrete and the sky; E. M. Forster, called Morgan, 43, was sexually and artistically frustrated; and D. H. Lawrence, called Bert, 36, had the threat of his books being banned (Women in Love, 1921, ” … ugly, repellant, vile”), and a libel suit against him so wanted to know “For where was life to be found” and thought by going to a quiet place by himself he might find it: Ceylon, New Mexico, or New South Wales.

All four had achieved some degree of literary fame: Woolf had published two novels and the third, Jacob’s Room, was waiting for her final revisions, however her illness kept her away from her work. Eliot had published successfully The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock in Poetry magazine in 1915 and had been a regular contributor of reviews and essays, primarily for The Times Literary Suppliment right up to December 1921. Forster had achieved great success with a series of novels, usually about the English aboard, beginning with Where Angels Fear to Tread in 1905 but by 1922 nothing had appeared after the very successful Howard’s End in 1910. Lawrence was more infamous than famous and had had Women in Love published in June 1921. It garnered bad reviews, and low sales. This added to the outrage caused by its prequel, The Rainbow, 1915; it was withdrawn by the publisher after it was banned under the Obscene Publications Act. Lawrence had also characterised in the latter work, an acquaintance, Philip Heseltine, and thought he had disguised him enough, but Heseltine was not fooled and threatened legal action.

For all four writers 1922 did not begin well.

Artistic endeavour is always trying to solve the problems of the art form itself. How does a writer write an autobiography and make it interesting without using the boring phrases, “Then I went …. she cried and so I said …., Then I said, and he went ….”? Novelists for centuries have been using description and dialogue to draw a character; but in an autobiography how do you create an image of the narrator. There must be another way? Yes, there is, and one of the first writers to find another way was James Joyce who began his autobiographical novel Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) like this

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo.

First of all he writes not in the first person, but in the third (very radical, this is an autobiography, remember) and the above opening is not dialogue, it is prose; it’s not said by the protagonist but by the narrator using the language that the little boy, James, might use to describe what he sees and what he sees is himself! It’s as if the third person narrator is not some all-pervasive, god-like know-it-all but an imp sitting on the shoulder of the little boy seeing the world through his eyes and hearing the thoughts in his head. This literary device has become known as free indirect discourse, or as the literary critic of The New Yorker, James Wood, calls it, ‘close writing’; and it’s as common today in contemporary fiction as Vegemite is for breakfast. But it can’t be used in the first person because the first person doesn’t need it.

It is not just new ways of expression that all writers look for but new ways to solve old problems. Woolf, Eliot, Forster, and Lawrence always had difficulties writing their next work even if their previous work was successful. “That worked! Why don’t you write one like that again?” remains the continual cry to all writers. Even Forster, the most commercially successful of the four of them, was always afraid of repeating himself.

Painters of the same period sought to bypass the ‘real’ bit in order to paint, say, serenity, by trying to paint serenity with just the paint on the canvas, not trying to be something else, a face or landscape, to ‘portray’ serenity. In other words, they painted not what they saw but what they felt. Writers similarly de-focused the ‘real’ bit and concentrated on, not what the characters did – the plot – but what the characters felt and thought. The plot became internalised.

Before January 1922 was over Eliot and Lawrence had succumbed to the influenza that brought Woolf so low and was rapidly becoming an epidemic to rival the devastating outbreak of 1918-19 that killed more people than the Great War. At least for Eliot the influenza kept him away from the bank and, despite the disease, hard at work on his long poem. His ill wife also being absent was yet another and usual worry out of the way.

On his way back to London from the unsuccessful trip to India Forster bought and read Proust’s first volume, Swann’s Way. He was “awestruck”. Woolf, with her illness almost past, read him in the spring while working on an essay about reading and dabbling with and reworking a character from her first novel, The Voyage Out, Clarissa Dallaway, into a short story called Mrs Dallaway in Bond Street. Both Woolf and Forster were enthralled with Proust’s use of memory to evoke the current state of mind of a character. In the opening scene of the short story, which eventually evolved into the novel Mrs Dallaway, Woolf has Clarissa arrested by the chiming of Big Ben which announces the convergence of the past and present, not only in the character’s mind but also on the page. Very Proustian! Clarissa Dallaway in Woolf’s first novel is described by the narrator but Woolf was determined in this one, this modern one, to have Clarissa think everything the reader needs to know about her. As Woolf wrote later to a friend, she didn’t mind being sick as “Proust’s fat volume comes in very handy.”

Woolf, who wrote that she wanted to write like Proust, didn’t of course, but it was because of him that she began to write like herself again.

Joyce was different. Woolf and Joyce were both the same age, and Joyce in early 1922 had “a novel out in the world, a massive – expensive – box of a book”, Ulysses, and Woolf had not published a novel in two and a half years. She was jealous. Bert Lawrence ran away to New South Wales and began a book where no one takes their clothes off, but since the libel suit against Women in Love was unsuccessful, the (negative) publicity sparked interest from readers and sales swiftly grow. Morgan Forster at home with mother burned all his “indecent writings” and embarked on a new novel, A Passage to India.

If the English literary world did actually break in two in 1922 it was because of Proust and Joyce. Proust’s monumental seven-volume À la recherche du temps perdu variously translated as The Remembrance of Things Past or In Search of Lost Time, and labeled in some quarters as the greatest novel ever written, came out in English and Joyce’s Ulysses, which began as a serial in an American magazine and consequently banned, was finally published in book form that year. It is also the year that Marcel Proust died. The major effect was on writing and therefore the literary novel took a turn to the introspective, to the experimental, to the perverse and in so doing left a lot of readers behind, sticking stubbornly to the realism of the previous century; and most of them still do. They want a painting of serenity to be paint on canvas masquerading as a face or a landscape. However, it is true that because of what happened to literature in 1922 the relationship between writer and reader was changed forever.

This is a fascinating book, well written, and full of information about writing and writers… if you like that sort of thing.

You can watch the charming and playful School of Life animated videos, narrated by Alain de Botton, on James Joyce here, Marcel Proust, here, and Virginia Woolf here.

Here, you can watch a short biographical video on T. S. Eliot, and you can watch a short video on D. H. Lawrence by Anthony Burgess, here.

You can download all the novels and short stories of Virginia Woolf, Marcel Proust, including all 7 volumes of The Remembrance of Things Past, James Joyce, and D. H. Lawrence, for FREE, here.

Here, you can download the major works of E. M. Forster, for FREE, and you wan watch a short film of Forster talking about writing novels, here.