The most remarkable thing about Cold Light, the last in the Edith Trilogy (Grand Days 1993, Dark Palace 2000, Cold Light 2011), and indeed the trilogy itself, is the woman, Edith Campbell Berry. She is the type of woman who, while working at the League of Nations in Geneva in the 1920s and visiting a Paris nightclub, slips lightly from the lap of a lone black musician and puts his penis in her mouth; falls for and marries a bi-sexual, cross-dressing, English diplomat but only after mis-marrying an American journalist who turns out not to be whom he seems; masturbates a mutilated war veteran as her deed for post-war reconstruction; hates the smell of keys, and who kisses her brother’s girlfriend on the lips. This is Edith Campbell Berry who in 1950 finds herself, aged in her 40s, living in Canberra “…about as far from the centre of the modern world as you can get without being in a desert … a slap-dash country of such unhappy food.”

If this mismatch isn’t mismatched enough Cold Light opens with Edith discovering her long-lost brother, Frederick, who is now a working member of the Communist Party which is about to be banned by the new Prime Minister, Robert Menzies. How’s a girl, with a lavender husband and a red brother supposed to get a job in this town? This is particularly galling for Edith who wants – believing she deserves it – a status-riddled diplomatic post, which was something then a married woman could not have no matter what colour her husband was.

Because of a few pulled strings, she gets an invitation to dinner at the Lodge, where she airs and wears her Chanel, but diplomatically tells the other wives ‘it’s a copy’, and gets a hand up her dress from the man on her left, something she relishes, and offered a job by the man on her right, something she despises, because it’s only a job of sorts: as ‘special’ assistant to Canberra’s Town Planner. However, despite its low status, really no status as all, she is inspired by the sketches of the Canberra dream made by Marion Mahony Griffin, wife of Walter Burley Griffin, and takes the job but insists on her own office, gets one, but one with no windows, and decorates it with bespoke furniture from Melbourne and a cumquat tree. She drinks Scotch, is a fastidious dresser, wears stockings under slacks, a Tam o’ Shanter, when necessary, and does her husband’s nails and lets him wear her silk nightie to bed.

Edith Campbell Berry is a hotel cat: mistrusted by a few, loved by most, but belonging to no-one. Her wish for a Bloomsbury life leads her to recognise a man for her, and so marries again, but after years that began passionately, her marriage slips into one of normality and routine (wonderfully and insightfully described by Moorhouse) and when confronted by a new Prime Minister, Mr Gough Whitlam, whose lieutenants know nothing of her, her ideas, or what she has to offer, she is then unemployed, discarded, and emotionally alone. However, her past does not desert her, and her experience as an officer of the League of Nations in Geneva (Grand Days), her work in Spain during the civil war and her position on a UN committee (Dark Palace), and her reputation in Canberra, mainly fuelled by incorrect gossip about MI5, ASIO and her truthful but unconventional life, comes to the attention of Whitlam. She is offered a position as an ‘eminent person’ to be a pair of eyes for the new Australian government in areas of international diplomacy and unease. She is delighted. This takes her to the Middle East where the book ends, surprisingly, dramatically, but really, so appropriately. No spoilers here.

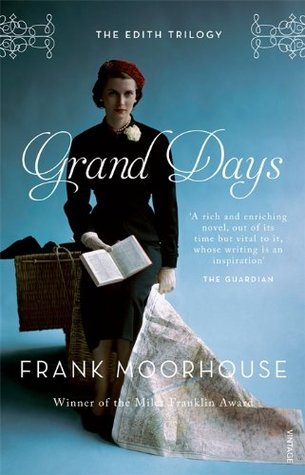

Frank Moorhouse is a living Australian writer who deserves to be better known. He has won the Miles Franklin Award (for Dark Palace) and many state and national awards as well. The Edith Trilogy is a major contribution to Australian literature where trilogies are rare: Henry Handle Richardson’s The Fortunes of Richard Mahoney (1917 – 1929) and Ruth Park’s Harp in the South (1948 – 1985) are ones that spring to mind. The books are big, Cold Light, is very big, but where Moorhouse excels is his tone and insight into love and all its shades, romance, sex, politics, human frailty, personal ambitions, and inevitable failures. All three books can be read in isolation but once you taste Edith Campbell Berry you will want to taste her again, so read them all. You won’t regret it and you won’t forget her.

You can buy the eBook here for $10.99, as well as the others in the trilogy.