I’m not a recipe-bound cook. I like recipe books for ideas not instructions. Generally due to this approach I produce eatable, sometimes interesting, but usually unmemorable dishes. However, sometimes I even amaze myself: my first soufflé was a triumph and I basked in my own pride, and praise from others. Usually, though, when I attempt a former triumph a second time, it is a disaster: my second soufflé was more like a biscuit.

I have seen evidence of this second-time-failure phenomenon in other human endeavours, and not just mine, but Patrick Gale’s second novel of 17, Ease (1985), is not one of them.

His first The Aerodynamics of Pork (1985) was a joy to read but Ease surpasses it: its simpler, clearer, better structured, and philosophically more interesting.

Domina (Dom, Min, Mina) Tey is a successful playwright, who lives with her long-time partner – too long to be a boyfriend, but not legal enough to be a husband – Randolf Herskewitz, (Ran, Rand, Randy – Gale loves to play with names). He’s a writer too, although an academic one, more truth-as-wonder than Domina’s truth-as-reality.

Min writes plays about “menopausal lecturers and novelists” for “the discerning Guardian-reading, professional-oblique-arty masses”, which Des (Desiree), her agent, loves and can sell, but Min is worried she’s getting bored, and therefore boring.

Min leaves Randy and leaves behind the loveliest ‘I’m leaving you/not leaving you’ note you have ever read: “I won’t be in for dinner for a few weeks but the freezer is well stocked,’ it begins. She goes to “visit herself” and “secrecy of whereabouts vital to success of spiritual growth” and she signs “Apologetic affec. Mxxxxxxx.”

She moves to “a top-floor bedsit by Queensway, with no view, in a house full of odd little men and an old-bag downstairs who used to be a mortician.” One of these little men is Thierry, a young, French, gorgeous, promiscuous, and very successful, homosexual who takes her on one of his sauna-searching escapades; another is Quintus, a young, sweet, naïve history student who is trying also to find himself but has just found God, well, not God really, more a church; and not just any church, the Greek Orthodox Church. He captures Min’s curiosity and she captures a few other little things of his as well. I won’t go on; no spoilers here, and there’s quite a lot I could spoil, but no.

No-one knows how this thing we call human life started, if only by a bolt of lightning in a pool of primordial ooze, but start it did, with or without a creative hand. It sounds unlikely but it only had to happen once in a multi-squillion or so years. Anyway, stuff happens and us humans have many diverting, equally unlikely, annoying, and definite views on how we cause or are affected by such stuff and what we then need to feel or do; but if you are of the philosophical bent of our protagonist, Min, (and Mr. Gale, I suspect) you may come away from reading this book with a more peaceful, uncluttered, and sanguine view of us, allowing you to get on with life, like washing the dishes, walking the dog, loving, reading and /or writing books.

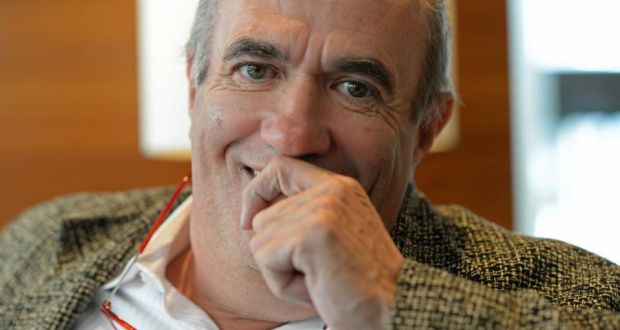

Patrick Gale is a British novelist whose ebook editions of his many novels are published in the US by Early Bird Books, and marketed by Open Road Media.