It has been suggested, more than once, that the greatest thought that mankind has ever made is that matter is neither created nor destroyed, it is just rearranged … endlessly. In other words, there is a finite number of atoms but an infinite number of their combinations. One of those combinations is you. This is one of the ideas of the Greek philosopher, Epicurus (341 – 270 BCE) and he got the idea from someone a little bit older, his teacher, Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BCE). It’s been around a very long time.

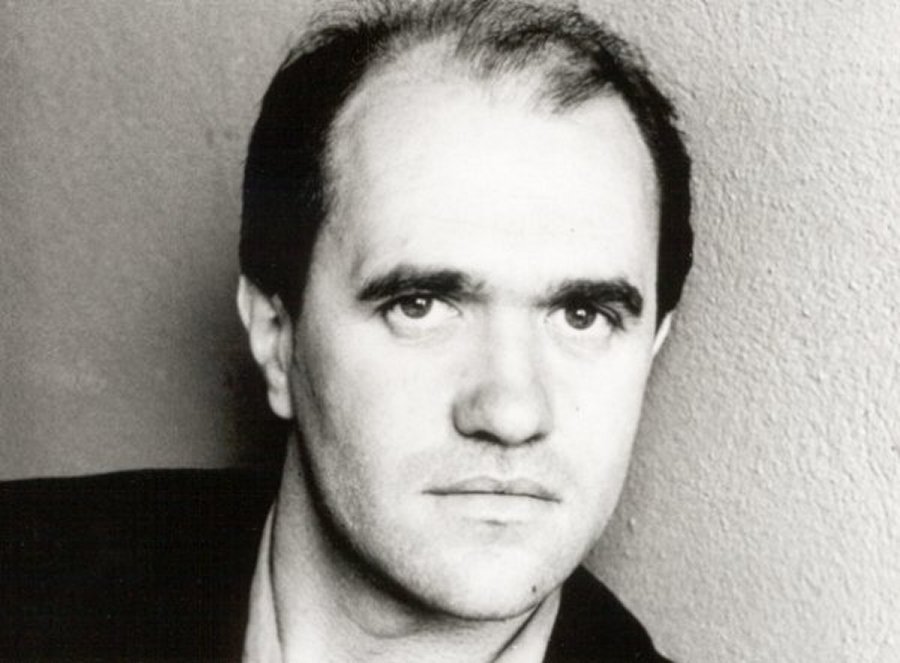

I’m a fiction nerd, but every now and again a non-fiction work, catches my eye. The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began (2012) is the story of Poggio Bracciolini (POH joh BRA cho LEE nee), a papal secretary, scribe and book-hunter, who in 1417 discovered a manuscript called De Rerum Natura (Of the Nature of Things) written by Lucretius around 55 BCE. It had been lost for over 1500 years. It was, is, an elegant and beautifully written poem describing the natural world in strong Epicurean ideas.

- The Universe has no creator or designer; everything comes into being as a result of a swerve, which is also the source of our free will

- Nature ceaselessly experiments ( this is the idea at the heart of Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection)

- Humans are not unique

- The soul dies and there is no afterlife; death is the cessation of all feelings, including fear

- All organised religions are superstitious delusions, which are invariably cruel

- The highest goal of human life is the enhancement of pleasure and the reduction of pain and the greatest obstacle to pleasure is delusion

- Everything is made of minute, invisible and eternal particles, atoms, floating in a void (scientifically proved by Jean Perrin, via John Dalton, Robert Brown and Albert Einstein, in 1909)

Like any passionate book-hunter, Poggio was ecstatic. He had it copied – he is also credited with designing the font we know now as Roman – and circulated. Of course, only to people who could read sophisticated Latin and that meant highly educated people who invariably were clergymen. In a world where all aspects of life: commerce, travel, governance, art, architecture, music and science were dominated by the Catholic Church, the discovery of this poem was like a bomb going off … slowly.

It influenced writers and thinkers for centuries: Leonardo di Vinci, Thomas More, Shakespeare, Milton, Spencer, Montaigne, Voltaire, Isaac Newton, Ben Johnson, Copernicus, Galileo, Thomas Jefferson, (he owned 5 Latin editions of the poem) to name a few. But the incredible impact of Lucretius’s poem is not only measured by the influence it had on writers and thinkers but, more importantly, by the multiple efforts the Catholic Church created to oppose it.

Greenblatt has used novelistic techniques to tell the story not only of Poggio and his discovery but also of the characters he interacted with and the times in which he lived and worked. This is not a dry academic tome. It is a lively account of how one lived and worked in the early years of the Renaissance. For example the Council of Constance was arranged to end the Western Schism (1378 – 1417): three men had claimed simultaneously to be Pope. It is estimated that over 100,000 people descended on the small German town, Dukes, royalty, administrators, ambassadors, cardinals, archbishops each with his own retinue of servants, cooks, maids, scribes as well as opportunists, singers, actors, barbers, acrobats and over 700 whores. It is an engaging and wondrous read.

Lucretius wrote that atoms did not move in a straight line but they randomly changed course. He called it a swerve. According to Greenblatt that is exactly what Lucretius’s text did: its trajectory was a straight line to oblivion, but it swerved and was found. Thousands of fragments and editions exist today all over the world.