A short story.

1

For Albrecht Meier the whole world jolted and slipped sideways one Monday morning in the early summer of 1950 when, walking to work to his machine job at the Pope Factory, he realized that the discomfort in his stomach wasn’t a tummy upset: he was in love with his wife.

This was unexpected and had not been part of the deal.

Back in 1926, The Meier family had moved to Neu Heim on the banks of the River Murray from Neale’s Flat several hundred miles to the west, on the ‘dry’ side of the northern Adelaide Hills. The small Nue heim settlement took advantage of the land between the main Loxton Road and the river and was a bastion of German Lutheranism where several families had settled. Freda Weiss was the third daughter of one of them: a wealthy family with extensive property at Neu Heim. However, the Meier’s new property was on the other side of the main road, again on the ‘dry’ side. Irrigation was in its infancy but there was certainly an advantage living ‘on’ the river and the Weiss family’s prosperity confirmed it, whereas the Meier family had to rely on the fickleness of the weather, and that took a social, financial, and personal toll.

Albrecht Meier and Freda Weiss had gone to school together at the local Lutheran Church. He once grabbed her bonnet off her head and stuffed it down the toilet hole in the school latrine, as a sign of affection. She understood this but acted outraged as was expected. However, she was removed from school to look after her frail mother who was expecting another child, but with three other daughters in the family, there were rumors of another more scandalous reason, so the gossip went. Freda and her mother were not seen at church for over seven months. Albrecht paid little attention to gossip. He read the Bible, played his cornet, and tended to his beloved horses and when he left school to work on the farm with his father and brothers, he had only seen her at church and community functions but paid little attention to her. He paid very little attention to any of the eligible girls in his community. He was always considered a serious type, obedient, helpful, a good boy. He considered that girls and all that was something for later when he was older. But being the youngest boy, he was usually overlooked, not with any punishing intent; he seemed to be self-contained and happy to be left alone so he had drifted to the periphery of his family’s attention. Finally, Freda, Mutti, her mother with a new babe, Freda’s brother, were welcomed back to church. Albrecht began finding himself planning on where he would sit in church so he could see her and maybe get a smile thrown his way.

When he became aware that his parents were discussing him, he also became aware that such discussions seemed to have been going on for some time, like he’d come in late to a kitchen conversation and, curiously, they included the eldest of the Weiss boys, Gerhardt; he was a friend of his brothers, but he had come to the house to talk to his parents. Albrecht soon discovered what was intended.

To say the marriage was arranged would’ve been too blunt for the religious sensibilities of the community, too old-fashioned; it was fostered, encouraged, and successfully so. What the couple may have thought about it no-one much cared. It’s what the families wanted; it’s what the families orchestrated and what the families prided themselves on achieving. He had not objected to the match; Freda was a handsome girl. It solidified the mutual respect of the two families – Albrecht was proud that his family was now considered at the same social level as the Weiss’ – and whatever the family wanted and needed he was willing to comply. Loyalty to family and God were, in his young malleable mind, as one and the same thing. He saw it more as a mutually beneficial understanding than a marriage. He would still have his horses, his cornet and piano, he would still work on the farm, and they would live in the Wappika cottage at the far end of the Schober Road paddock. It was even further away from the river but still on Meier land. It never occurred to him what Freda might feel about it; he assumed she consented to the arrangement and was part of the understanding. Women’s opinions were as unconsidered as foreigners. He was aware of the necessities and pleasures of marriage and wasn’t ignorant, nor frightened, of his sexual responsibilities but he was a little surprised, and vaguely worried, at his new wife’s ardour on their wedding night but, like most men, he concluded that it had more to do with him than with her and resolved that the Christian thing to do was to be more matter-of-fact.

That was over twelve years ago and three children since then: Reiner, a fair-headed boy was born in 1934, followed by Lowden, a dark-headed boy a year later. Reva Marie, a rosy-cheeked curly blond-headed girl, was born rather unexpectedly, in 1942.

2

‘Hey, Lowy!’ said Reiner, in a whisper as loud as a cocky.

‘Sssh! Dad’ll hear.’

He tried again. ‘We gotta go!’

‘It’s too cold.’

‘Yeah, a bit, but the pigeons’ll be sleepy coz, and easy to snatch.’

‘We’ve got to get there first.’

‘It’s all set. Fair dinkem. Ol’ Scratchy Bum’s fence is all set to go. I got it ready before tea.’

‘It won’t work.’

‘L-o-w-y,’ said Reiner threateningly in his big-brother voice.

The two boys slept head to toe, toe to head in a bed in the sleep-out: the side veranda was closed in with wooden walls and louver windows of bubble glass. It used to be Rainer’s but since their little sister, Reva, came along, Lowden’s bed went to her in what used to be his room, in the house, so the boys had to share: one under the sheet, one on top. They weren’t told why, but Rainer knew that Lowy was still very young and still had baby germs, so that must’ve been the reason. Rainer was the oldest so his name couldn’t be babyfied but Lowden, Lowy, wasn’t just the younger, he was also the used, Rainer the user, but sometimes the slave, but always the follower.

Rainer’s plans always got Lowy into trouble.

Little Reva had been a baby and so out of their thoughts for a hell of a long time. Months! Her full name was Reva Marie but that was a bit of a mouthful, ya tongue tripped over itself so she became just Reva. Reva was enough! But she had growed-up quick and wanted to join in their games, mainly Cowboys and Indians. It was always Cowboys and Indians like on Saturday arvo at the pictures. Mum forced them to let her play with them or else they’d get a hidin’ til their legs went red, but really they found her useful, with them as the Indians, hootin’ and shoutin’ with chook feathers in their hair and slapping their hooting mouths with the palms of their hands which was what real Indians did – everybody knew that – so she had to be the cowboy who was tied to the Hill’s clothes-hoist, but when she kicked up a stink about always being tied up with the kindling stacked ‘round her feet screaming blue-murder when they lit a match Mum made them make her the Indian, so they did, and put chook feathers in her hair an’ all, but she couldn’t hoot and shout because she was still tied up to the clothes-hoist as the two cowboys skipped and slapped their thighs and danced around her like real cowboys always did in saloons and stuff, and still Reva screamed and yelled sounding no way what a real Indian would sound like. Reva was never satisfied with her role. She was a girl.

Their school was down the street and around the corner a ways, but as the crow flies, it was near as a neighbour but you had to climb on the chook-house roof, jump over one fence, through a pumpkin patch, over another fence with the help of Ol’ Jock’s apricot tree, down a lane full of leaves, rats, and bits of rusty bikes, and then through the back paling fence of old Mrs. Overden who they called Ol’ Scratchy Bum coz she was forever tugging at her ‘lastic coz her undies kept stickin’ in her bum crack.

On Saturdays, sometimes, the boys were allowed to go on their own to the Odeon Theatre just around the corner in David Terrace, and down a bit, but if the boys were really good, which wasn’t often, they were allowed to go on the tram by themselves into the city to the pictures, buy an ice cream or a biscuit, and back on the tram again; all for sixpence. Oh, hey! When ya had to write sixpence ya had to write it with the letter ‘d’ after the number which was really stupid coz the word ‘penny’ started with a ‘p’ not a ‘d’ but that’s what the king who lived in England said ya had to do, so, because the king in England said that, that’s what ya had to do which was really stupid. But that’s kings for ya.

Anyway, Rainer had to look after Lowy, and he took his role very seriously. The tram was a real rickety thing – that bucked and rocked whenever it started off and had to stop. The wheels were in the middle not at either end, so whoever designed it like that needed his head examined. That’s why they called it the Rockin’ Billy! A little boy who wouldn’t hold on like he was told to could be easily bucked off and go head first into the traffic! Reiner had to hold onto Lowy’s hand as they got on the tram and Lowy always wanted to sit near the door so he could see the cars going past but Rainer made him sit right in the middle of the tram as far away from the door as possible because he didn’t want Lowy to fall off – there were no doors; but not because he was afraid Lowy would get run over, flat like the pennies they put on the tram tracks to watch them buckle and pop as the tram went by, but because he would get a hidin’ from Dad if he didn’t do what Dad said: he had to look after his little brother, which was what big brothers were supposed to do. It was a rule, Dad’s rule.

Rules had to be followed coz Dad said that’s the way the world works. He called it an axiom. Dad knew some strange words. He worked in a really big factory where he made sprinklers and other water pipe stuff. Rainer knew not to ask stupid questions, so he worked it out for himself. He knew that some words were related but had different endings, like god and godly, and some words went together like sauce and sausage, so he reasoned that the word axiom had something to do with axle; and he knew that if you broke an axel the car wouldn’t go so he kinda understood what his Dad said about rules. But that didn’t mean he never broke them. And that’s why there had to be The Black Mariah that hung behind the kitchen door, when Dad wasn’t using it to sharpen his razor, that is. And that’s another thing. He knew about rules, but he also knew that he broke some. It was like there was two Reiners, one who knew the rules and one who kept breaking them. This was a confudlement: another word he heard in a book. He couldn’t ask Dad coz he’d get – Don’t ask such stupid questions – and he couldn’t ask Mum coz he’d get – Ask Your father – but like all confudlements he knew that everything would become clear when he was a grown-up. But he also knew that some grown-ups did stupid things. There were some new people, English people, who lived in the lean-to off the side of Charlie Berendt’s place: the cobbler, and someone said that in summer when it got really hot the English people hid under the bed because they thought the hot sun would set them on fire. That’s really stupid! Didn’t they have a sun in England? And they were grown-ups! Well, some of them. Maybe they didn’t have sprinklers in England. They should see their king about that.

‘Lowy! If you don’t get up right now I’ll give you such a Chinese burn!’

‘It’s dark.’

‘Of course, it’s dark, you nincompoop. It’s midnight! Come on!’

‘Oh, Jeez Tosser,’ whined Lowy. The girls at school were always hanging around Reiner and called him Tosser coz he kept flicking his forehead curls out of his eyes with a toss of his head. Tosser he became and Tosser had stuck.

The two boys eased themselves out of bed trying not to make the bed-springs creak and put on what clothes they could find in the dark. It didn’t really matter what clothes they put on; they were all Rainer’s. Getting the louvers out of their slots was trickier still but within five minutes or so they were out of the sleep-out, grabbed the stashed potato bag from its hiding place, over the chook house, and on their way.

When they got to Ol’ Scratchy Bum’s place, they knew exactly where she kept her ladder, propped-up behind the laundry, and when they got to her back fence, ‘Hey Rainer, these palings are already loose,’ whispered Lowy. ‘Y-e-a-h! I told ya, dumb-bum. I did ’em before tea. Come on!’ And with great and silent care they maneuvered the ladder and themselves through the fence and into the school yard. This was territory Rainer knew as well as he knew the freckles on Lowy’s face. Within minutes he had the ladder against the stone wall of the toilet block and was shimming up to where the pigeons were roosting on top of the stone wall under the corrugated iron eaves. It was easy. Before you could say Bob’s Your Uncle, Rainer had six pigeons and a couple of handfuls of twigs, feathers and stuff in the potato bag and they were scurrying at each end of the ladder back to Ol’ Scratchy Bum’s laundry with the bulbous bag full of fluttering pigeons bouncing against his back. All they had to do was pop them in the little pigeon coop they’d tacked together that afternoon, out of chicken wire, veggie boxes, rusty nails, and binder-twine on the side of the chook-house. The twigs, feathers, and stuff made the birds feel right at home.

Jeez, they were clever. Here was their little business. At a tu’pence a pop there was more than a bob’s worth cooing and snuggling into their new home. And this was just the first night! Wait till they see the look on Dad’s face when Rainer says, No, Dad, put your sixpence away, we don’t need ya money for the pictures. We’ve got our own!

3

The Pope Factory, in Charles Road, Beverly, was only a thirty-minute walk from 419 Torrens Road, down David Terrace and across the Port Road. There was a second-hand black Ford Anglia E04A 2-door saloon in the garage at Number 419 but like some of the crockery in the kitchen cabinet and some of the clothes in the wardrobes the Ford Anglia was only used for best: to church on Sundays and the yearly trip to Nueheim on the Upper Murray to see their relatives.

Albrecht, Al, never liked to be late so always gave himself enough time in case of unexpected delays which could be all kinds of things: he once had to help a lady find her dog. It had crawled under the house and Al had coaxed it out with a kind voice and a bit of bread and cold mutton from his lunch box. He had always been good with animals. And then last year a small truck had collided with a tram and being a responsible Christian man, he had to go and see if he could help. But, to Al’s mind, not in all the world would he have imagined that of the ‘all kinds of things’ that could be considered as ‘unexpected delays’ could they possibly include this falling-in-love thing. It amazed him, but what amazed him most was that there was pain involved. Actual physical pain, like a stomach-ache after too much chocolate but sharper, hotter. It made him take deep breaths as if his lungs were tied all of a sudden. The tinny ding-ding of a tram made him look up and he realised he’d been standing on the side of the Port Road for, well, he had no idea how long he’d just been standing there. And then he knew why he felt like he did: the thought of losing her.

4

Reva Marie was an independent little girl. She had to be. Her house in the mornings was frantic: both Freda and Albrecht went to work – Freda worked at the local ACTIL Cotton Mills a few blocks away at Woodville – and the boys had to be wrangled to get them off to school. There was shouting and banging around, hot words sometimes and bad language, well as bad as language could get in a God-fearing Lutheran household. ‘Damn’ and Hell!’ were verboten and would lead to a hiding, or the threat of one if time was short, which it usually was in the chaotic mornings. The worst of the language was from Rainer ‘Bloody Hell!’, and usually under his breath so only Lowy or Reva heard it. Reva said a little prayer for him, but Lowy took on Rainer’s sin as yet another burden at being his younger brother. Reva, to escape the mayhem, simply went over early to the house next door where her grandma lived. Freda’s parents had helped finance their house, but no-one ever talked about that. Bertha Weiss – Grandpa Weiss had died and gone to Heaven before Reva was born – was a tiny old woman and she looked forward to little Reva Marie coming over in the mornings and helping her get breakfast, setting the table, making the tea, buttering the toast, and learning a lot about what went on in her daughter’s house. Just before Reva’s sixth birthday, on a rare occasion when both households were together, someone had asked her what she wanted as a present. She said, without hesitation, that she wanted to go to school. No-one expected that. Who would take her? The boys didn’t want to. The parents had to go to work. And Bertha would miss her dreadfully. She was a girl, so education was never considered important. Reva Marie wasn’t fazed by this and simply said she would get herself to school. And she did.

Reva Marie, aged six and a bit, and tall for her age, finally started in Grade 1, the oldest in the class, and the brainiest, because she started so late and had already discovered the magic and magnetism of books and also was aware that what adults said and did, did not always match. Now she was almost nine and no more a little girl, still shorter than her brothers but far superior in every other measurement.

On Friday she was walking home, no one came to get her, the boys just ran off and left her, as usual; they wouldn’t be seen dead walking with a girl! She didn’t mind; walking home alone gave her a lot of thinking time and Reva Marie loved her thinking time very much. So, she was walking alone again on the footpath along Torrens Road, thinking about if those sparks she had seen once at her dad’s foundry had anything to do with the stars in the sky, they looked so alike, when she heard a noise. It was like a voice and not like a voice, a cry but not like a cry. She wasn’t sure what it was, but it seemed to be coming from a big hibiscus bush that spilled over a low garden fence onto the footpath. She stopped and looked at the bush, and then she made her eyes look into the bush. The leaves were dark green, and the flowers were big and very red. She parted a branch or two and that’s when she saw her. A little girl. Hiding in the hibiscus bush. She had small eyes, a button nose, and a small mouth, all on a very round face. Her once blue dress was grubby and a bit torn. She was wearing a little apron that wasn’t doing much to protect anything. Her hair was fine and mousy, straggly and needed a cut.

‘What are you doing hiding in a bush?’ said Reva Marie.

The little girl had a silly look on her face as if she had done something wrong. ‘I’m not hiding,’ she said. ‘I’m waiting.’

‘Waiting for who?’

‘… you?’

She seemed to be asking her if she was the one she was waiting for. She didn’t know. Was she?

‘Where do you live?’

The little girl didn’t answer. She didn’t want to say but shook her head; she shook her head slowly at first but then faster and faster until her whole body was shaking to and fro. She really didn’t want to say.

‘Your Mum will be worried about you.’

And she swayed her whole body again as if to say really loudly, ‘No, she wouldn’t!’

‘So, what am I going to do with you,’ sighed Reva just like her mother did when exasperated by the boys coming inside with muddy shoes.

The little girl held out her hand, offered it to Reva Marie who could see narrow welts on the little girl’s palm. She saw what Reva Marie was looking at and snatched her hand back real quick and hung her head and just stood there.

‘Alright then,’ said Reva Marie. ‘Come with me,’ and she reached and took the little girl’s hand. ‘Come on! You can’t stay in a bush!’

A little smile crinkled the little girl’s tight mouth, and she went with Reva Marie, hand in hand down the footpath along Torrens Road like two little girls walking home from school. To the little girl it felt like heaven, like home: the closest she’d ever come to being with someone.

As they were getting nearer to Number 419 Reva Marie thought she saw her mother standing on the footpath outside their house. As she got nearer she saw that it was her mother standing outside their house. And with a suitcase by her side. Reva Marie walked on with the little girl in tow until she got to Grandma’s house, next door to hers. She stopped. ‘Mum?’ she called, frowning.

Freda Meier’s head jolted in her direction. She was crying!

‘M-u-m?’ repeated Reva Marie.

Just then she heard a noise, a knock on glass, and turned to see her Grandma gesturing to her to come in. Freda Meier heard and saw the old woman, her mother, too. She picked up her suitcase and hurried back into her own house without a word.

Reva Marie didn’t know what was going on. Her Grandma knocked on the window again and gestured emphatically for her to come inside. So, she did, dragging the little girl with her.

The girls walked down the side of Grandma’s house and under the thickly leafed grape vine that covered the unused driveway. It was early summer, and Reva Marie could see the forming bunches of grapes, tiny now, like lace, but soon there would be plenty to eat, if they got to them before the birds. Grandma Weiss, hair piled on her head and wearing a large, brown-checked bibbed apron that covered almost all of her, was holding the back door open with one hand and she had a rag, an old man’s singlet, her dead husband’s, in the other. As the little girls walked in Reva Marie could smell vinegar: Grandma had been cleaning windows. They waited by the kitchen table.

‘Who’s this then?’ asked Grandma Weiss.

‘She’s lost.’

‘What do you mean, lost?’

‘I found her in a bush.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous. What’s your name, girl?’

The little girl shrunk against Reva Marie.

Grandma looked annoyed with pursed lips, ‘Cat got your tongue?’ The woman took a deep breath and put on a smile. ‘Now, little one, you must have a name. Everyone has a name. What shall we call you?’

The little girl looked up and then at the table where lay an open magazine to pictures of a really big house on one page and a full-page picture of a beautiful smiling woman on the other. She had really thick eyebrows. The little girl reached up and pointed at the picture of the woman.

‘Who’s that?’ said Reva Marie.

‘Acht! Some brazen actress,’ said Grandma as she closed the magazine. It was The Australian Home Beautiful, price one and sixpence. ‘Well, I suppose, one name is as good as the next. Joan! Shall we call you Joan?’

The little girl nodded her head.

‘Then Joan it is. Right! Reva Marie, you make the tea. You know where the biscuits are. And Joan here needs a wash and some clean clothes, so you come with me. Grandma took Joan’s hand, but little Joan wouldn’t let go of Reva Marie.

‘It’s alright Joan,’ said Reva Marie, ‘Grandma has boxes of children’s clothes out in the garage for the Lutheran Ladies Trading Table. You can choose something you like.’

Joan was convinced (a choice!) and let go of Reva Marie’s hand.

‘First things first,’ said Grandma. ‘There’s your little dirty moon-face to take care of, young lady, and other bodily bits no doubt. Come with me, little Joan.’

Grandma pulled the little girl out of the kitchen towards the bathroom and Reva Marie put the kettle on, got out three cups and saucers, the Elysee everyday set, not the Kobenhavns, which was only for best, and fetched the gollywog biscuit tin from the kitchen cabinet and put it on the table.

Some thirty minutes later, Little Joan, in a pale cream frilly dress with yellow roses around the hem and a white and pale blue cardigan, sat at the table, legs dangling off the floor and ending in white socks and little brown shoes.

‘Don’t eat so fast, Little Joan, you’ll give yourself an ache,’ scolded Grandma, as gently as she could, which wasn’t very. ‘Come and sit here, Little Joan. Come on!’ And she pulled the girl from her chair and up onto her lap, then dragged her cup of tea and saucer in front of her. ‘There we go! And only dunk your biscuit once, and very quickly or it will all fall into your tea and make a mess.’

Reva Marie felt a pang of something new: jealousy. It was common family knowledge, true or not, that Grandma Weiss wore, and had always worn, a cast iron girdle around her waist, and Reva Marie had for years longed to sit on her Grandma’s lap to see if the story was true, but Grandma Weiss’s lap had not been for sitting on, until now. Reva Marie looked sternly at the little girl sitting where she herself wanted to be.

‘Now, Reva Marie, your mother!’ continued Grandma Weiss. ‘She’ll be the death of me, that woman! So, what’s she up to now?’ and in preparation for what she assumed she would hear she put both her hands over Little Joan’s ears.

*

Later that Friday evening when Albrecht got home from work Reva Marie was setting the table and had put the pot of yesterday’s mutton stew, flavoured with a heaped dessertspoon of Keen’s Curry Powder, back on the stove which sat within the old bricked alcove made especially for it. Little Joan sat and watched. Reva Marie’s interview with Grandma hadn’t lasted very long because she didn’t know the answers to any of Grandma’s questions.

The boys were out the back tending to their pigeons and showing them to Mrs. Dietrich and her little boy Alan. Mrs. Dietrich was the Lutheran Pastor’s wife and a very important person. Alan Dietrich was pasty and thin and had been beaten up by Reiner twice, but the need for pet pigeons was far greater than his fear of Reiner, who was as charming as spilt honey. Mrs. Dietrich had bought a pigeon two weeks ago for Alan and now was back for another. The boy’s little business was flourishing it seemed. When Reva Marie introduced Little Joan to her brothers, Lowden said, ‘Hello Little Joan’; Reiner said, ‘Not another one!’ but when she tentatively introduced her to her father, Albrecht Meir was more interested to know where his wife was than what a strange little girl was doing at his kitchen table. His questions about Little Joan would have to wait.

‘Mum’s in the bedroom,’ was all Reva Marie said, when asked. She had told him what she had seen but, of course, what she had seen was very little. Reva Marie noted the stern look on her father’s face as he disappeared out of the kitchen. Practical girl, she went to the stove and moved the pot of stew half on and half off the stove; she anticipated a long wait until teatime.

Albrecht waited outside the bedroom door, thought a bit, decided not to knock, and went in.

Freda Meier was sitting on the bed, back to the door, head down, but she whipped it around at the sound of the door opening and closing.

‘I don’t want any of your self-righteous clap-trap,’ she said. He noticed she was wearing make-up, now smudged, and had on one of her old Sunday dresses. He also noted the suitcase on the floor.

When he didn’t answer she got up off the bed, turned to face him, stood erect, meeting his gaze. She was a determined woman and her stance said she was prepared for what she thought was coming.

Al walked slowly towards her. She stiffened. He took out a handkerchief from his trouser pocket, reached and held her chin with his left hand and began to wipe the wet eye-makeup from her cheeks.

‘You don’t need to wear this stuff on a weekday,’ he said, quietly but not unkindly.

This was one of the things she hated about her husband: his control. She would’ve preferred shouting.

When he was finished, he folded his handkerchief and put it back into his trouser pocket.

‘That goes in the washing,’ she said.

He ignored her and pulled out the chair from under the dressing table, sat and looked at her. ‘Tell me,’ was all he said.

She decided to fight control with control. She sat back on the bed which didn’t feel like control at all; it felt like too much giving in. She wasn’t sure what was appropriate. She stood up again. ‘I’m sick of it. Sick of it!’ Her mouth was tense trying to keep her voice down but also letting him see her frustration. It came out sharper than she had intended.

‘Sick of what?’

‘All this. The boys are running wild and getting into all sorts of trouble. Mrs. Overden says they broke her ladder and Old Jock over the back swears they cracked a branch of his apricot tree. I can’t control them. And you do nothing. You working. Me working. But chump chops instead of cutlets. Stew instead of steak. Why? A new car in the garage we never use,’ and holding out her skirt, ‘The Lutheran Ladies Trading Table instead of John Martins. Why?’

‘We’re saving.’

‘What for?’

‘You know! For the future. A better life.’

‘Where is this better life?’

Albrecht thought of Stan Jacobson who said he knew of a place.

‘When is this better life? When?!’

‘When the boys reach leaving age so they can help.’

‘What, in a business?’

‘Could be. I don’t know yet. There’s time.’

‘There’s your time. What about my time.’

‘Reiner will be thirteen soon.’

‘Next year.’

‘Alright then. Next year. That’s not too long.’

‘Not for you. What about me? I want something better. And sooner! I used to live in a five-bedroom house.’

‘Of course, you lived in a five-bedroom house, there were seven children.’ Albrecht stood up and went to grab her hands, ‘Freda.’

‘Don’t touch me.’ She wanted to remind him that his family had six children and only three bedrooms, but the moment had passed.

Albrecht looked at her and then at the suitcase.

‘What’s this then? Hm? You want someone else to touch you?’

‘How can I let you on top of me when I’m so angry with you?

‘Don’t talk like that.’

‘You and your damn piety. Do you think God has time to watch what we little people do in the dark, and only when you want to?’

‘He knows everything.’

‘Then he certainly knows how I feel.’

‘Lasciviousness is ungodly. Besides, we can’t afford another child.’

‘Hm! It needn’t be for a child.’

His body jigged. His face went dark. His mouth fell open. ‘What did you say?’

Luckily, there was a knock at the door. They heard Reva Marie’s earnest voice through the door, ‘Daddy?!’

‘Not now Reva,’ said Albrecht over his shoulder, throwing the words at the door.

‘But Daddy, it’s Mrs. Dietrich.’

‘Who?’

‘Mrs. Dietrich. Pastor’s wife. She’s a bit upset.’

Freda turned away from him.

He sighed. ‘Alright. Coming.’ He turned to face his wife. ‘Freda.’

She turned to face him.

He pointed at the suitcase and said, ‘You will tell me about this.’ He left the room.

‘I showed her into the lounge room,’ Freda heard Reva Marie say to Albrecht. She sat on her dressing-table chair and looked at herself in the mirror. She opened a jar of Pond’s Cold Cream and scooped out a large dollop, looked at herself again, and smeared cold cream all over the mirror, smearing her reflection.

Mrs. Dietrich was standing in the middle of the living room. Her boy Alan was cowering by her side, looking terrified.

‘Mrs. Dietrich,’ said Albrecht with a smile as he entered and saw the woman. ‘How nice to see you. I hope Pastor is well.’

‘Very well thank you, much better than I, Mr. Meier.’

‘Oh, I’m sorry to hear that. What appears to be the trouble?’

‘This, Mr. Meier, is the trouble,’ and she held out her hand in which was firmly grasped a pigeon.

‘Is it not healthy?’

‘Oh, it’s very healthy, Mr. Meier. It’s as fit as a fiddle.’

‘That’s good.’

Her face crinkled. ‘Mr. Meier, are you aware of your boy’s little enterprise?’

‘Yes, Mrs. Dietrich. They sell pigeons for pocket money.’

‘Yes, they do, and I bought one for my Alan and because he loved it so much and wanted it so badly I paid one shilling for it.’

‘I see. That’s a bit expensive, I agree. I’m sure we can give you some of your …’

‘That is not the point, Mr. Meir,’ interrupted Mrs. Dietrich.

‘No?’

‘No. Alan’s pigeon was doing very nicely in the little aviary Pastor Dietrich built for him but one day Mrs. Anderson’s cat took an interest in the bird, so we became very protective of it. Alan even gave it a name, didn’t you Alan? And what did you call it? Alan?’

Alan said something.

‘Speak up Alan and look at the person you’re talking to. Haven’t I taught you that?’

Alan slowly looked up at Albrecht and said, ‘Peter, Mr. Meier.’

‘That’s right. We called it Peter and had a little name tag made, but we had a little mishap with the door-latch, didn’t we Alan?’ and she looked at the still withering little boy beside her, ‘and that led to his escape and, we assumed, he became lunch for Mrs. Anderson’s cat. Alan was devastated! So, what did we do? We came back to your boys. Mr. Meier, to get another pigeon. And we found one. This one. Very similar to Peter, in fact, and paid another shilling for it. Alan was delighted especially when we saw this,’ and she grabbed one of the bird’s legs and held it out to reveal and small piece of a bandage wrapped ‘round the little leg and with the word ‘Peter’ written on it in red ink. ‘It’s not just similar to Peter, it is Peter. Do you understand Mr. Meier?’

‘Certainly, Mrs. Dietrich.’ Albrecht’s face was like approaching thunder.

‘Selling and re-selling homing pigeons to little boys, Mr. Meier, may be a country custom but it certainly isn’t a city one. This is fraud, Mr. Meier. Fraud! I demand instant reparation, or I’ll call the police, and they will understand who exactly I’m talking about. They know the names of your boys, Mr. Meier, believe you me.’ And Mrs. Dietrich, having said her peace, stood with hands clasped before her and head held high expecting instant attention.

‘Reva Marie!’ called her father. She had been hovering in the background. Little Joan had retreated behind the kitchen door.

‘Yes, Daddy.’

‘The change tin, please.’

Reva Marie ran to the kitchen, dragged a kitchen chair in place, climbed up on it, took down an old Sunshine Powdered Milk tin from the mantlepiece over the stove, and ran with it towards the living room. She saw Little Joan cowering behind the kitchen door, but she would have to wait; Reva Marie hurried into the living room. Albrecht Meier held out his hand. Reva Marie found a shilling in the tin and put it in the palm of his hand. He looked at it and returned his hand to Reva for more. She searched among the pennies and halfpennies and found two sixpences which she added to her father’s hand. He checked the amount and handed the coins to Mrs. Dietrich.

‘Please, accept my apologies Mrs. Dietrich.’

She took the money. ‘Thank you, Mr. Meier, and I sincerely hope you will deal with your boys in an appropriate manner and return them to the Christian path of fairness and good will. I don’t mind telling you, in fact it’s my Christian duty to say so, but your boys are running amok, Mr. Meier, and need a much firmer hand. Pastor Dietrich only talked about this yesterday. Gooday, Mr. Meier. Come with me Alan, and here, take this.’ She held out the dazed bird to her son who took it willingly.

‘Reva Marie, open the door for Mrs. Dietrich,’ said Albrecht Meier.

Reva Marie dashed past Mrs. Dietrich. The front door was hardly ever used so Reva Marie had to tug at it to get it open. The woman waited and as her proud head was held high anyway she saw the trim tailored grey velvet curtains and her eyebrows flicked up at the trio of swags that expensively graced the window top but then her gaze dropped to the grey-green eucalyptus design of the lounge suite and her nose twitched.

‘There we go, Mrs. Dietrich. Bye, Mrs. Dietrich,’ the girl said, her struggling with the door having succeeded. ‘See you at school, Alan.’

‘Come on Alan, and walk properly,’ and the woman, and son with bird, left the house.

When Reva Marie finally got the front door closed again Albrecht Meier was already gone. She heard his loud and commanding voice from the back yard, ‘Reiner! Lowden!’ and then noticed that The Black Mariah, his shaving strap that usually hung on a peg behind the kitchen door, was missing.

Reva Marie went to the back screen door and opened it to see her father standing patiently waiting for the boys, the Black Mariah dangling from his right hand.

‘Shall I see if I can find them, Daddy?’

‘They’ll come,’ he said quietly with confidence, without turning around. Reva Marie returned to the kitchen to give the lamb stew a bit of a stir and then remembered Little Joan. She was gone.

Minutes later, Albrecht Meier was swinging the Black Mariah down on the backs of the boy’s thighs as they stood bent over in the kitchen next to the stove, with their pants around their ankles. Lowden was crying but Reiner’s face was screwed tight shut.

Albrecht straightened up and took a breath. ‘Where’s the money?’

Reiner slowly stood and said slowly, ‘In Reva’s play-house, under the roof.’

‘Lowden.’ The younger stood, still sobbing, and pulled up his pants. ‘Bring it to me.’ The boy walked uneasily. ‘And don’t dawdle!’ The boy scampered out the door.

Reiner bent down to raise his pants. ‘Not yet my boy,’ said Albrecht as he pushed the back of the boy’s head onto the table, and he gave Reiner an extra whack, thinking – and that’s for being so bloody stupid and not taking off the silly nametag!

‘What was that for?’ said Reiner through gritted teeth.

‘Never you mind!’

Lowden, still with a screwed up teary face, came back with an old Jaffa packet and handed it to Albrecht. He weighed the contents in his hand. ‘How much?’

‘Two pounds four shillings and sixpence,’ said Reiner slowly.

Albrecht was impressed but didn’t show it. Instead, he reached up for the Sunshine Milk tin on the mantlepiece, opened it and tipped the packet full of coins into it. The sound was loud and final and felt to Rainer as his birds all flying free. ‘Go to your room. No tea for you tonight.’

‘Aw Dad!’ whined Reiner. Lowden sobbed.

‘Go!’ and the boys fled the kitchen. Albrecht didn’t move until he heard a door close. He put the shaving strap back on its hook behind the kitchen door.

5

Reva Marie knew there was going to be further trouble between her parents. She was sitting in the lounge room bravely reading a book called Thimble Summer, which Grandma had got for her from the Lutheran Ladies Trading Table. Her mother didn’t approve of reading when there were jobs to be done, and there were always jobs to be done, but Reva Marie was emboldened by her Mum still held-up in the bedroom; but she couldn’t concentrate because of what was going on in the kitchen, and she couldn’t read in her room because being in her room during the day felt like she had done something wrong, and she was very careful about that. She thought about her Dad belting her brothers and her Mum on the street with a suitcase and wondered what it all meant. She then remembered something, something nice, something that gave her hope, one time months ago, and she wondered what had changed.

She wasn’t sure why, but she’d found herself suddenly one night sitting up in bed rubbing her eyes. She felt something was wrong – was there a noise? – but was then heartened by the ribbon of lounge-room light she saw under her closed door. Reva Marie got out of bed and walked and slowly opened the door, careful not to bring attention to herself. She saw the back of her father’s armchair where he was sitting. Her mother was sitting on the arm of his chair with her left arm resting over the chairback and onto his left shoulder. It was a calming image. She could see her mother’s right elbow moving in and out and thought she must be rubbing her father’s tummy. He had indigestion sometimes after tea and she must be rubbing it for him, just like she did to Reva when she had a stomach-ache from eating a too-green apricot given to her by Ol’ Jock over the back fence. She thought she heard her father say something, but her mother’s left hand moved and grabbed his arm but then her hand went to her father’s head, and she ran her fingers through his hair and then rested her head against his as she shifted her position slightly towards him, to do more affecting rubbing, Reva Marie thought. ‘There there,’ Reva Marie heard her mother say, or something like that. She must be doing a good job because her father was not moving now and seemed content, but then he did move, and Reva Marie closed her door and listened to the sounds of two people getting up and walking to their bedroom. Reva Marie hoped her mother would remember about the Epson salts in the kitchen cupboard but then maybe, she thought, her father was feeling better and was now ready for bed.

Reva Marie’s anxiety at waking in the dark was completely gone so she climbed back into bed and felt a calming feeling of gentle hands and soothing voices. She went back to sleep very easily knowing full well that everything was as it should be. Nothing was wrong at all.

Where was that feeling now? she thought.

6

After the meting out of justice to his two sons and sending them to their room without any tea Albrecht Meier opened a bottle of Southwark, drank half of it and wiped his mouth. He didn’t know where Reva Marie was. She was looking for that little girl, he thought. Albrecht returned to the bedroom, more business to sort out.

Freda had been sitting at the dressing table. She had taken off all her makeup and the suitcase was unpacked and back under the bed. The mirror glass was clean again. She brushed her hair, stopped, looked at herself, stood up, reached under her skirt and took off her stockings and underwear, and sat with the clothing in her hands. She heard the door open and quickly put the items in the top drawer.

She heard the door close.

‘Tell me. What were you planning to do?’ he said.

Freda had thought about what she might say, what she should say, and what she couldn’t. She turned to him. ‘What do you think it’s like for me? I feed you all, pack lunches for you all, work at the mill all day, feed you all again, day after day, and my pay goes in the bank every week out of my reach, and you don’t touch me anymore.’

‘Oh, Freda,’ groaned Al Meier as he sat on the bed with his head in his hands.

‘Oh, don’t give me that ‘Oh Freda’ business as if it’s you who’s so hard done by. And that bitch Sally Coots hits my break whenever my back is turned, and all my yarns snap and I have to stop the machine and re-feed every spool and start it up again.’

‘Why do you get their back up so much?’

‘Because I’m married! To you!’ she spat a little too vehemently than she wanted. ‘They suspect what kind of man I’ve married who sends his wife to work. And they’re jealous of my week’s count, so much better than theirs, and the attention from Bill …’ She didn’t mean to say that.

‘So that’s his name?’

‘Bill Karras is a good boss and gives me privileges because I’m the best spinner he’s got. They’re just jealous because he won’t give them a second look.’

‘And I suppose he looks at you more …’

‘He looks at me a whole damn more than you do.’

‘Stop it!’ He looked at her sitting there staring at the roses in the carpet. ‘You were going to leave us.’ He said it as if it was the just-discovered answer to a whole sway of little questions. ‘And he didn’t show up.’

‘It’s always been clear to me when I’m not wanted.’

‘Oh, don’t talk such rubbish. You’re a wife and mother.’

‘You don’t want me.’

‘You have a family.’

‘Oh, so it’s keepin’-it-catholic now is it? What does that make me? Chief cook and bottle washer.’ She got up and knelt in front of him, between his knees and grabbed his belt and attempted to undo it.

‘Freda! Stop it!’

She continued and then tried to undo his fly.

‘Freda! Don’t!’

‘I’m your wife. I’m allowed!’

‘And I’m your husband and I say no!’

‘Why?’

‘It’s not right.’

‘Why?’

‘God says.’

‘God never had sex. How would he know?’

‘Don’t blaspheme! Freda!’

She stopped but stayed on her knees.

‘We agreed to a plan,’ he said to change the subject while he redid his belt, ‘double pay for as long as it takes to get the money.’

‘What money?’

‘Enough.’

‘How much is enough?’

‘As much as it takes.’

‘To do what?’

‘To be my own boss. Make a go of something.’

‘Of what?’

‘It’s not clear yet.’

‘You must have some idea.’

For emphasis he raised his hands in the air, ‘I don‘t know. Not yet.’

She took the advantage and swiftly finished pulling down his fly.

‘Freda!’

But she got her hand in and into his underpants.

He grabbed her arm but she had her hand full. He closed his eyes as if concentrating to control himself. She moved her hand.

‘Freda,’ he said through clenched teeth.

‘Oo. Someone might not want to but something else does.’

‘I’m asking you to stop.’

‘Why? It likes it.’

‘It’s an abomination.’

‘No-one’s watching,’ she said softly, and her hand kept moving.

‘God’s watching.’

‘No, he’s not. Besides, he created me.’

‘It’s a sin.’

‘You can pray for forgiveness in fifteen minutes.’

She stood, pushed him back with force and straddled him and got him inside her.

It seemed he only had one other course of action: he swung his arm and slapped her hard across the face, more from reaction than reason. She staggered back off of him and against the wardrobe. She was stunned, then angry, and stared at him with contempt, lying there exposed.

‘You look ridiculous!’ She shouted, ‘Get out!’

‘Freda! I’m sorry but look what you made me do!.’ He got off the bed and rearranged and tidied himself. ‘Freda, I’m so …’

‘Go sleep in the lounge room.’ Her voice was low and determined. She reached and grabbed a pillow from the bed and threw it at him. ‘Here!’

‘Freda, be reasonable. We have to talk this through. I won’t sleep on the couch and you’re upset so you won‘t sleep either and we’ve both got to work tomorrow.’

‘I don’t.’

‘Why?’

‘I quit.’

‘When.’

‘This morning. Get out.’

Now, he’s angry. He picked up the pillow from the floor, turned and grabbed his pajamas that were under his pillow, stood next to her and said, ‘Excuse me.’ She stood aside. He opened the wardrobe and grabbed a blanket from the top shelf and his dressing gown from a hook behind the door and left the room.

She suddenly knew she had to act quickly: she raced out of the room, across the passage to the bathroom and locked herself inside. She needed to be alone in a hot bath.

Albrecht opened the door to Reva Marie’s room and went over to the sleeping child. He sat on the edge of her bed and gently woke her.

‘Oh, Daddy, is everything alright?’

‘Yes, Sweetie, everything’s fine. Where’s that little girl?’

‘She’s sleeping at Grandma’s. It was quieter over there.’

‘I see. Did you say your prayers?’

‘Yes, Daddy.’

‘Good girl.’

‘Go back to sleep.’

‘Yes, Daddy,’ and she snuggled down, and he tucked her in.

In the small hours of the morning, unable to sleep, Albrecht with his dressing gown loosely over his pajamas walked into the kitchen. The only light was the little cooking light over the stove in its bricked arch and the glow of soft coals through the stove grate. The fire in the stove never went out. His wife, in her nighty, was standing, barefooted, next to it spooning mutton stew into her mouth from the big pot. He walked up behind her. His hands twitched because he wanted to hug her but was afraid to, because of where it might lead.

‘Freda,’ he said softly.

She turned around and looked at him. She presented him, his mouth, with a spoonful of lukewarm mutton stew. He opened his mouth and she put the heaped spoon of stew in it. A bit of gravy dribbled down his chin as he chewed. She used a finger to wipe it off and then sucked it.

‘You were going to leave me,’ he said gently.

‘Treat me like a wife and I might stay.’

‘You have to pray for forgiveness.’

‘What I pray for is my own concern. As is yours.’

‘I’m sorry I hit you.’

‘Well, that’s a start, I suppose,’ and she turned back to the pot of stew and reached in for another spoonful. He leaned into her and sniffed her hair, closed his eyes, but wrapped his dressing gown more firmly around his body. She chewed the meat, savouring its earthy taste, turned off the stove light, put the spoon in the sink, and walked to the door; she stopped, turned, looked at him in the gloom of the streetbright from Torrens Road through the kitchen window, and left the room. He couldn’t see her eyes. Albrecht Meier didn’t know what to do. He stood there for a moment confused and hating it. Eventually, he returned to the living room but saw that the blanket and pillow had disappeared. He breathed a sigh of relief and walked to the bedroom, lit only by her bedside lamp. When he entered, Freda was putting the blanket back onto the top shelf in the wardrobe. His pillow was back in its place. He took off his dressing gown and hung it on the hook behind the bedroom door. Freda was getting into bed and then he did. She turned off the light. They both lay there staring into the dark. Not touching.

‘We are doing good. We are blessed with two incom …’ Freda imagined she could hear his brain cogitating, working against her; It’s all she could expect. ‘You must ask for your job back. You are respected there. You told me. You get bonuses more than the other women. That bloke. He lied to you. Whatever he promised. He lied. He owes you. Get your job back. Another two years. Another two years and we’ll have enough. Enough to do something … do something … something … grand.’ Freda couldn’t see his lips as they lovingly formed that word and the satisfaction of it in his eyes; all she heard was the hollow sound that word made in the dark. Grand. He, nor she, had ever used that word, would never use that word. It was a book word. A word that sounded like a foreign language. He lay there welcoming the earned sleep he could feel was so close and imagining all kinds of what that word, grand, could be, and he prayed that whatever that word could mean it would someday be something in front of him that he could see and call his and know that God had given it to him. Because he was a good man, and he was soon asleep.

She rolled away from him wondering how he could sleep so quickly and so well when her mind was all awash with broken promises, mutton stew that needed more salt, and men who looked, really looked at her. She so wanted another hot bath.

7

On Saturday morning, Albrecht got out the push-me lawn mower and pushed it all over the front lawn. He did most of his thinking while pushing the thing. The boys, forbidden to go to cricket practice and under strict instructions, were pulling down the pigeon coop on the side of the chook house. The remaining birds flew in some confusion and rested on the chook house roof cooing, pacing, and watching their home disappear. Freda and Reva Marie were doing the washing; Little Joan watched on intrigued; boiling the sheets in the copper; hearing the machine chug-chug; she watched in amazement as the cube of Ricket‘s Blue dissolved in rivulets of ultramarine between the folds of linen in the final rinse; and then Reva Marie feeding the whites through the wringer as Freda turned the handle with one hand and wiped her brow with the other. It was a modern process. Meanwhile Albrecht pushed the mower and thought what to do.

Over lunch of cold meat, left-overs, and buttered bread, after Albrecht had said grace, he laid out the plan for the rest of the day. Little Joan wasn’t listening but was trying hard to get the tomato sauce out of the bottle onto her plate but got it on the tablecloth and her cardigan instead. She tensed with terror, but Reva Marie just licked a hanky corner and tried to get the stain out but made it worse. Albrecht talked over this little girls’ domestic drama. The boys could go to the pictures at the Odeon on David Terrace for the Saturday afternoon matinee. The two of them nearly whooped out of their chairs but rules about children remaining silent at the table kept them relatively quiet again. Their eyes bulged with pleasure, but soon died: they had to take Reva Marie and Little Joan with them.

‘O-w D-a-d!’ escaped from Reiner, Lowden’s mouth fell open.

Albrecht cried through gritted teeth, ‘Quiet!

Little Joan winced.

‘And you, Reiner, Lowden, will look after them,’ he added. ‘Understand?’

‘Yes, Dad,’ said the boys like robots.

And Freda knew exactly what was going to happen. Albrecht wanted to know all about Bill Karras and the suitcase. They would be alone together for at least two hours.

Albrecht got the Sunshine Powdered Milk tin from the mantlepiece and watched the boys as he counted out the coins: what was the boy’s money was now his money. He counted out enough for four tickets, and extra for four Amscol Ice Cream Dandy cups, and without the boys knowing he added an extra two sixpences and placed the handful of coins in Reiner’s hand. ‘You’re the oldest, Reiner, and you now have responsibilities. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, Dad.’

‘Good.’

‘And Reva Marie,’ said Freda, ‘get another cardigan for Little Joan. I’m sure Grandma has plenty in that box of hers.’

‘Wait!’ said Albrecht to stop the children shifting off their chairs; don’t you know what has to be done? He lowered his head, folded his hands, and closed his eyes, as everybody else did; Little Joan was a little slower and not yet used to the ritual. ‘We thank You, Lord for this our food and health and life and all that’s good.’

‘Amen,’ they chorused.

‘Ah men,’ said Little Joan.

And the children rushed from the table.

‘And comb your hair!’ called Albrecht after the boys.

Freda started clearing the plates.

Reva Marie and Little Joan ran to Grandma’s house next door. Bertha Weiss was cutting up kuchen and wrapping the large pieces in a damp tea towel before putting one in the fridge and some in a cake tin.

‘Hello Grandma!’ said Reva Marie.

‘Hello Grandma!’ said Little Joan.

‘Good day to you young ladies,’ said Grandma dusting her hands together which was a habit of hers.

‘We’re going to the pictures?’ said Reva Marie with some excitement.

‘What’s the pictures?’ said Little Joan?

‘You’ll see!’

‘It’s not like your father to take you to the pictures on a Saturday,’ said Grandma.

‘The boys are taking us. Dad said.’

‘Are they now? Will, Little Joan, you can’t go out with that stain on your cardigan.’

‘Mum said you might have another one.’

‘I see.’

And just then, Freda came into the kitchen and said, ‘Just a minute, Little Joan. Give me that cardigan, please. I’ll get that stain out while you’re out.’ She was looking for things to do this afternoon.

‘Are you sure, Freda, the boys can look after them?’ asked Grandma as Reva Marie helped Little Joan take off the stained cardigan.

‘Albrecht seems to think so.’

‘I can look after Little Joan,’ said Reva Marie.

‘I’m sure you can,’ said Grandma, ‘but who’s going to look after you?’

‘Me!’ said Reva Marie confidently.

‘Yes, because you’re such a big girl all of a sudden. Now take Little Joan to the garage and find her a clean cardigan.’

‘Yes, Grandma,’ and she took hold of Little Joan’s hand. ‘Come on.’ They left the kitchen. Freda turned to go.

‘I want to talk to you about Little Joan,’ said Grandma forcefully to stop Freda leaving.

‘What for?’ she said matter-of-factly.

‘I think it best that Little Joan comes to live with me,’ said Grandma in her mother-knows-best voice. Freda’s face took on a look of disdain. ‘She can have her own room and here it’ll be much quieter for her. I can only imagine what was going on in your house yesterday, she ran over here, away from heaven knows what! Here I can give her the Christian guidance she needs. I hate to think what other horrors she ran away from.’

Freda said, even before she realised that she had, ‘Still collecting other people’s children I see.’

Bertha Weiss, like a knee-jerk, slapped her daughter’s face. ‘Don’t be so ridiculous, Freda! That mouth of yours will be the end of you, my girl.’

Freda, with thunder on her brow and a hand on her cheek turned to go.

‘Wait!’ called her mother.

Freda took a deep breath and turned.

Bertha Weiss handed her a large piece of Kuchen wrapped in a damp tea towel. ‘Here.’

Freda knew she now was obliged to say a polite ‘thank you’ as any good daughter should. She hated being polite to her mother and so wasn’t. She snatched the cake and left the house.

‘Acht!’ said Bertha Weiss with disgust.

*

Reiner and Lowden Meier walked together on the outside of Reva Marie and Little Joan, as they had been taught to do, to protect the girls from speeding cars sending waves of dirty water all over them. But it hadn’t rained in twelve days. Reva Marie wore a pink and white dress with smocking around the top that Grandma made; Grandma made all her clothes. Little Joan had two dresses now, so she wore the cleanest one. Grandma thought spoiling little girls was wrong: little girls needed discipline and to know their place. But as soon as they turned left from Torrens Road into David Terrace and out of sight of the house, Reiner bolted ahead shouting, ‘Come on Lowy!’

‘Tossa!’ yelled Lowden.

‘What?’ called back Reiner who stopped and turned, several yards ahead now walking backwards.

‘We have to look after the girls! Dad said!’

‘Yeah, I know, but we will. We will! But first come and see if Bandy’s there.’

‘We gotta stay with the girls,’ said Lowden walking nicely with his sister and Little Joan.

‘Don’t cha wanna see what’s on?’

‘We’ll know soon enough,’ said Lowden

Reva Marie was amazed. Lowden was standing up to Reiner and Reiner wasn’t liking it. Lowden and the girls were almost up to where Reiner was, and the boy looked like he had ants in his pants so eager was he to get to the theatre and see what was what.

‘Reva can look after Joany, can’t ya Reva?’

‘Dad said we had to!’ shouted back Lowden. “We’re in enough trouble this weekend without gettin’ in any more.’

‘Jesus Lowy! Hey! Look! There’s Jock Cunningham! Come on. Lowy, he wants to be our mate!’

‘Give us our money, Tossa!’ yelled Lowden.

‘Dad gave it to me coz I’m the oldest.’

‘Yeah, well, if you’re running off by yourself ya gotta give us our money.’

‘Oh, bloody hell, all right.’ And Reiner reached into his pocket and handed over some coins.

‘And for the dandies!’ demanded Lowden.

Reva Marie looked up at Lowden with much admiration. She’d never seen him like this before.

But that’s when Reiner noticed that there was a shilling more than expected. His face lit up.

‘What?’ said Lowden.

‘Nothing!’ said Reiner quickly as he pocketed the coins he had left. ‘You’re a chum, Lowy. You can look after the girls. I’ll see ya there,’ and off he ran.

‘Save us our seats!’ Lowden yelled after him.

But he yelled back, ‘Bars the seat on the end!’

‘Wow, Lowy,’ said Reva Marie.

‘What?’ he said.

She took his hand.

‘Don’t hold me hand,’ he snapped. ‘Come on!’

They walked towards the crowd of teenagers and kids outside the theatre all separated into groups by age, clothes, gender, and religion.

‘There’s Beryl Cunningham and Josie Black, Lowy,’ said Reva Marie. They like you.’

‘What?’ said Lowden with a worried face. ‘But they’re Catholics!’

Lowden was used to all the girls flocking around Reiner, well that’s what happened when he was with him. Reiner was the popular one, the cocky one; he hadn’t ever thought girls wanted anything to do with him, but he was an attractive boy, tall and dark, and soon to be a handsome one. Anyway, that’s what Josie Black thought.

‘Hello, Beryl, Josie,’ said Reva Maria.

‘G’day Reva,’ said Beryl, an elegant girl with hair like Judy Garland. ‘Hello, Lowden,’ she said shyly.

‘Hello, Lowy,’ said Josie, who Reva was sure was wearing lipstick, and not as shy as Beryl.

‘G’day. G’day,’ said Lowden awkwardly.

‘Can we sit with Beryl and Josie, Lowy?’ asked Reva Marie.

‘Yeah, Lowy, we’d like that,’ said Josie, smiling up at him.

‘Sure would,’ added Beryl.

‘Dad said I have to sit with my sisters,’ said Lowden.

Little Joan looked up at him as if he were an angel.

‘Yeah,’ said Beryl Cunningham, ‘that’s what we mean. We can all sit together.’

‘Oh,’ said Lowden, a little confused about what that might mean. ‘Er … well as long as we leave a seat for Reiner.’

‘He won’t sit with us, Lowy,’ said Reva Marie.

‘Well, Dad said,’ is all Lowden could say.

‘Come on then,’ said Beryl.

‘You can buy me a Dandy, Lowy’ said Josie.

And like it would be for the rest of his long-life Lowden Meier did whatever the girl he was with wanted him to do.

They bought their tickets and found seats on the aisle. Lowden made sure he left a seat for Reiner even though he was nowhere to be seen, but when the usher in his jacket and a pill cap, epaulettes, and a tray of Amscol Dandy ice creams came by, with hot ice spewing dripping smoke down on the floorboards Lowden stood up and went to the aisle and bought as many Dandies as he had money for. When he turned around to the row Josie was sitting in Reiner’s seat. He didn’t know what to do but Josie took a Dandy saying, ‘Thank you very much Lowy. You’re a real gentleman.’ As he sat down next to Josie, he gave the other dandies to Little Joan and Reva Marie, but she said into his ear. ‘It’s alright Lowy, you have mine, I’ll share Little Joan’s, she can’t eat a whole one.’

There was nothing for him to do but take the ice cream as Josie Black snuggled into him as the lights went down and the theatre was filled with cheering, catcalls, and the soft whoosh of Jaffas flying through the air and their tumbling rolling on the floor under the seats. The noise was deafening. Little Joan shrunk with worry in her seat and hid under Reva Marie’s arm. She had never been in a place like this in her entire short life.

And then out of the darkness the screen filled with grey and white light and loud trumpity music.

First up was a newsreel which was not very popular at all. Boos and yells filled the air. Post war building projects, farms with acres of carrots or beans, and new power stations were not of interest to anyone. A number of scuffles broke out up the back and Lowden was nervous with concern for Reiner and kept looking around for him.

But then coloured lights and different music filled the theatre, jolly and loud and Little Joan was enthralled on a completely different scale. The colours reflected in her dark pupils of her wide-open eyes.

It was a Tom & Jerry cartoon with Jerry the cheeky mouse bamboozling and thwarting Tom the cat at every turn. Every time Tom was squashed against a wall, stretched around trees, flattened by a steamroller, or tied in knots with a garden hose the crowd screamed with delight. The victories of the little guy sank sweetly and early into their mushy brains.

At interval when the lights came up there were children running everywhere. Ushers and Usherettes were kept busy selling ice creams, sherbet bags, lolly bananas, musk sticks, and White Knights bars. Beryl surprised everyone with a bag of raspberry jubes which she passed around.

When the lights went down again, another barrage of screams and shouts of approval filled the room and there was a moment of complete darkness; Little Joan shrank even lower in her seat, but then a man in a red suit in a spotlight appeared on the stage with a microphone and said in a sing-song voice, ‘Is everybody happy?’ and a thundering ‘Y-e-a-h!’ deafened little ears. Little Joan stuck fingers in hers. ‘Are you all going to be good?’ asked the man in the red suit. ‘Yeah,’ said most; “Ooooooo!’ chanted the oldest mob; ‘Maybe,’ said a few; and then the whole lot laughed, and all the seats swayed and creaked. The man in the red suit called out ‘Quiet Please!’ and he got a clamorous echo back ‘Quiet Please!!’ and lots of hooting and laughing. The man in the red suit just stood straight and waited. And waited. And waited. And the audience finally quietened knowing that the picture wouldn’t start until it did. Finally, the man signaled to someone up the back and his spotlight went off and the screen was filled with grey light again and ‘Buster Crabbe The King of the West’ in glorious black and white (Hooray!) with loud music of trumpets and drums, and then the title filled the screen ‘in Ghost of Hidden Valley’ which caused more cheering and hooting.

The story was simple: an Englishman, Henry, comes to take up his inheritance of Hidden Valley Ranch not knowing that, to the locals, it’s haunted and because of the local superstition a local farmer, Dawson, and his rustling gang are using the abandoned farm to keep their stolen cattle. Henry catches the eye of Dawson’s daughter who knows nothing of her father’s dastardly deeds. But Billy, Buster Crabbe, and his sidekick, Fuzzy, come to the rescue. The good guys wear white hats, and the bad guys wear black hats; there’s fist fights, (shouting and cheering), gun fights (more shouting and cheering), a kidnapping (Oh no!), a little romance (Ooooooooo!), a little comedy, (He’s behiiiind you!), but no Indians! This didn’t go down too well with the older boys in the audience who got restless, and scuffles broke out; boys chased boys up the aisle and the brouhaha grew.

Lowden heard in the dark, ‘Hey! Lowey!’. It was Reiner. ‘There you are! Come on, Lowey! That bloody what-not Morrie Dickson needs a thumpin!’ and he tossed his blond curls out of his eyes with a flick of his head.

‘Hello, Tosser,’ said Beryl Cunningham leaning forward. ‘We’ve saved you a seat,’ she loudly whispered.

‘Come and sit-down Tosser. We’ve gotta look after the girls,’ hissed Lowden.

He threw a limp smile back at Beryl. ‘Nah, Lowey! Girls are girls. Come on, ya gotta back me up. Shit!’ and he ran off as a pair of boys lumbered out of the grey darkness and chased him further back into the dark at the back.

‘Don’t go, Lowey,’ urged Reva Marie.

‘I gotta, Reva. He’s me brother,’ and he dashed out of his seat and into the dark.

The raucous continued until the noise of the film was drowned out by the noise of the fight: screaming girls and breaking wood, thumps and blows. Kids stood up and moved to the back so see what’s what. There was shouting and cheering but not at the action on the screen, but at the action at the back in the dark.

Little Joan was scared enough at the gun shots from the screen but now she started to cry at all the noise so close as she didn’t understand what was happening.

‘Come on, Joan,’ said Reva Marie, ‘we’d better go,’ and she led the little girl along the row.

‘Don’t go Reva,’ says Beryl, ‘it’s just boys being boys.’

‘Little Joan needs the toilet,’ said Reva Marie, ‘We won’t be long,’ and she said a little prayer for the lie and got to the aisle and out the side ‘Exit’ door. As the hand-in-hand girls hurried down the side street and reached the corner of David Terrace they saw a police car pull up outside the theatre.

‘Oh no!’ cried Reva Marie.

‘What’s wrong, Reva?’ said a worried Little Joan.

‘Don’t you worry. We’ll just walk home and then everything will be alright,’ but she had to wait until all the policemen got out of their car and … Reva heard a noise and looked back down the lane to see girls and kids rushing out of the theatre into the lane. ‘Come on!’ and Reva Marie tugged at Little Joan, and they hurried past the front door hearing shouts and crashes as they went.

Reva Marie couldn’t go as quickly as she would’ve liked but as they hurried home as fast as Little Joan’s little legs would let them, Reva Marie was thinking fast. When they got to Grandma’s house she stopped, bent down to the little girl’s worried face and said, ‘Now, you just go into Grandma’s and tell her that the picture was a bit scary, so I brought you home. It was a bit scary, wasn’t it? All those guns and that,’ and Little Joan nodded her head remembering it all far too clearly. ‘That’s right, that’s right. That’s the truth so there’s no need to tell her about the boys. Alright? Because you were really scared about the noise and the guns,’ and Little Joan nodded her head again. ‘Good. So just go inside and tell Grandma about the scary noise and the scary picture, alright? I’ve got to see my Dad about something important, so you go on now,’ and she let go of her hand and Little Joan walked up the driveway confidently knowing exactly what she had to do, and she disappeared into the shade of the hanging down grapevine.

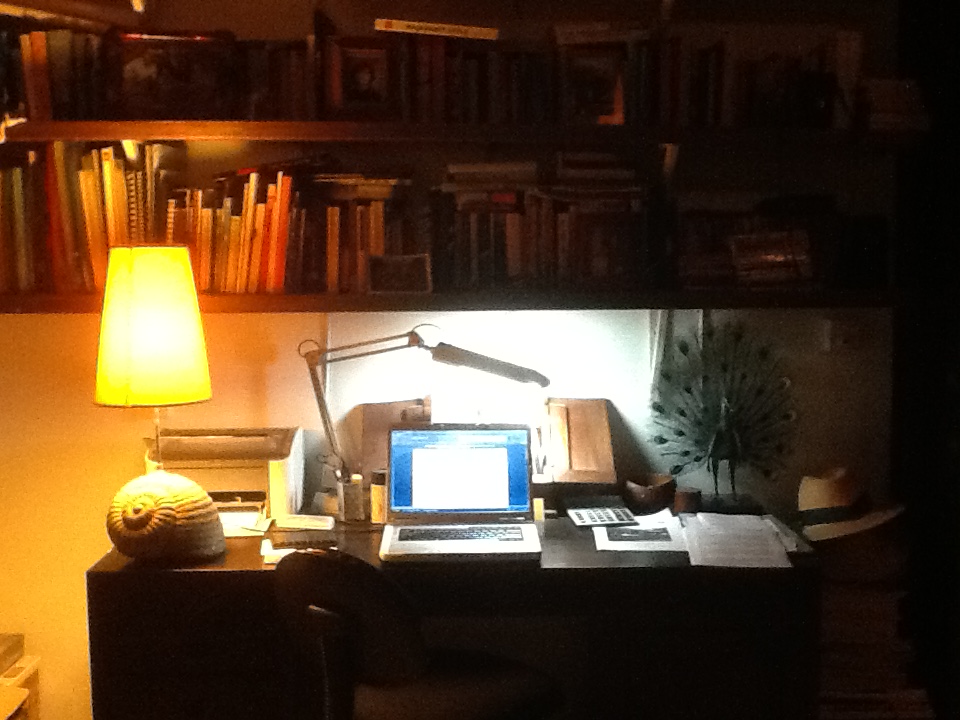

Reva Marie hurried to her house but when she got to the back door she could see through the flywire door; there were her mother and father sitting opposite each other at the kitchen table looking like they were having a serious conversation; no-one was talking but they were sitting as if they had or would very soon. She went to her playhouse. Her father had built it for her a year ago. She walked inside because that’s where she did her really good thinking about things and she had a lot of thinking to do at the moment. Her doll Molly in her pretty blue and white dress was lying in the dust amid a few pigeon feathers looking rather dishevelled and all her tea-set things were not how she had left them: neat and tidy. The boys had been in here.

And that reminded her. Reva Marie remembered what she had seen through the little playhouse window a few days ago: Reiner. She was going to say something like ‘What do you think you’re doing in my playhouse? It’s only for me, Dad said!’ but before she could say anything she saw what he was doing. She saw him from behind. He was sitting on the ground with his legs stretched out in front leaning against a post and had Molly in both hands and he was jigging her up and down on his lap. Reva Marie had no idea what he was doing but she thought it was something very strange and Reiner was making little grunting sounds that Reva Marie did not like one little bit. He was hurting Molly, but Reva Marie sensed that he was doing some boy thing that scared her. She was in a quandary but decided not to say anything.

But now she had something else to think about and she pulled and tugged at Molly’s clothes, smoothing her cheeks, and brushing her dress. She knew it was best to say something to Dad about the boys because he would know something had happened when he saw them; he always knew. Their faces were like the pages in a picture book.

She heard a noise. She wondered how long she had been sitting in her playhouse thinking about Molly and the boys and things. She hurried out and scampered down the side of the house as she heard more noises, the same noises: car doors slamming. When she saw the police car outside the house, the car, the police, and the boys, she gasped and ran back to the back door and into the kitchen. Both parents looked up as she banged into the room.

‘Dad! Something happened at the pictures, but it wasn’t the boy’s fault really it wasn’t it was … erm … it was … er … Morrie Yeah! Morrie Dawson who started it but it got very noisy, and Lowden went to help Reiner but Little Joan got scared because … er … the picture was scary not the fighting or anything but she had to go to the toilet and so it wasn’t their fault because …’ but her wide-eyed outburst was halted by a loud knock knock knock and everyone looked towards the front door. No-one used the front door; everyone always came around the back; no one used the front door except the Jehovah Witnesses and … When Reva Marie heard the ominous scraping of her father’s chair on the lino as he stood up, she ran. She ran back out the back door and over to Grandma’s place, where Little Joan was, where it was safer, and she stayed there for a very long time.

8

The Lutheran Church at Cheltenham was a modest peaked roofed single storey building with a simple pale brick façade and in the centre a Christian cross of glass bricks, and a squat faux bell tower. Women in modest hats, gloves, and swaying handbags; men in dull suits with hats in their hands; boys in shorts, shiny shoes with Brylcream in their hair; little girls in lace collars, frilly dresses, and ribbons wandered into the building, greeting everyone, the men shaking hands, the women politely nodding; all sweetness and smiles and Christian fellowship and all belying what really went on at home in the six days between now and when they were last here.

The Meier family was no exception. In fact, Albrecht Meier was the Secretary of the church council and a singer in the choir. His base voice booming out over all the others. On certain Sundays he was also a Lay Preacher reading a prepared sermon when Pastor Dietrich had duties in the sister churches of the broader Lutheran district. They went to church every Sunday with Grandma Weiss in tow, and that particular Sunday with Little Joan as well. She had no idea what was going on.

The interior, in true Lutheran style, was unadorned, as was the liturgy, involving standing-up chanting and singing and sitting down listening. The hymns were simple tunes in a narrow vocal range as they were sung by non-singers; a lot of them written by J. S. Bach and some by Luther himself. The sermon was the highlight of the service, but only in structure, not in enlightenment. Albrecht tried to listen to understand the sermon, to find its relevance, as was expected, but it wasn’t easy; Freda rested her eyes and counted her grievances; the children quietly fought over the Fantales Freda kept in the bottom of her handbag among the hankies, peppermint Lifesavers, lipstick, and lint for the specific reason of keeping the kids quiet during the Sunday service. At least they had something to read. And Grandma sat somewhere else, so she didn’t have to put up with her naughty grandchildren. Everything Little Joan saw and heard that day was new for her. When they had to stand for the praying bit Reva Marie bent down to Little Joan and whispered in her ear, ‘Just close your eyes and think of all the things you would like to happen and if you’re a good girl they will.’ Freda turned and looked at Albrecht whom she knew was praying for forgiveness for his weakness of the flesh, sure that his gently moving lips were sending prayers about her to heaven and hating it. Freda just prayed for plain old understanding. The children mostly prayed for the sermon to finish, when they would leave the adults and attend Sunday School in the little church hall behind. Little Joan went too, tottering along holding Reva Marie’s hand and wondering where they were going now.

To Albrecht, God was as part of his life as his right arm and the Church was at the centre of that part of his life. Family life was too complex and undulating with difficult decisions and compromises that unnerved him. But the Church was secure and never-changing. It gave his waking hours structure and solid boundaries within which he felt safe. The meaning of life, the moon, communists, atoms, aeroplanes, and algebra held no mystery for him because he had God in his life.

Freda, also believed in God, unfathomable though he was, but she couldn’t for the life of her quite believe that he was interested in the daily goings-on of little people, especially within a marriage that she had been taught was a God-made arrangement. Her attempt to free herself had failed. She felt her husband had failed her and Bill Karras had certainly failed her, but her biggest failure was not to get her way with these men, when she knew that she was very capable of doing so. She didn’t understand this yet as her self-esteem had taken a battering and she felt she was close to giving in. Is this what I get for marrying a Meier? She looked at the cross of light on the wall behind the plain altar and gained no succour from it at all. But she did feel some comfort from her view of all the people sitting around her. She looked at them, the backs of them, their clothes, the men’s combed hair shiny from too much Californian Poppy, the women’s cheap hats, their stories – the ones she knew – and her mouth pouted a little (she wasn’t aware of this) and she raised her head a little higher: she knew she was better than any of them.

9

So, now, on this Monday morning, walking to the Pope Factory, all that had happened over the weekend swirled around in Albrecht Meier’s brain creating a vortex of trapped problems without any outlet for solutions. Yet, the change in Freda baffled and excited him since it was part of the biggest problem, yet he now realised he didn’t want to lose her, he loved her. He was in love with her, but that concept was unknown to him; he didn’t read novels and the only film he had seen was The Song of Bernadette which was screened a year or so ago in the church hall preceded by a lecture on the Catholic-ness of the story and not to be ‘persuaded’ by it. Despite all that worry in his head his mood was buoyant which was a mystery to him, but he had always been a calm man, a stable man; he’d put it down to his Christian faith. That was his understanding of himself. He had not yet realised that his brand-new connection with his feeling about Freda was why he felt so, so, alive.

When he arrived at the Pope factory in Charles Street, Beverly, he was not late, but late for him. He went straight to the foundry where he operated a pipe press making parts for sprinklers and irrigation fixtures. This had been a promotion for him since during the war the press had been used to make components for munitions, but since his name was a German one, he was not allowed to use it so his promotion had to wait. Technically it wasn’t a promotion, his pay didn’t increase, but he took it as one. The press was already in operation by one of the ‘boys’; the bunch of underlings employed by Pope for £1/6s a week instead of the £6/1s a week, the basic wage for adults. It was because of Pope’s boys that the factory was known locally as The Boy Farm.

‘Hey! Sooty,’ cried Albrecht, ‘What do you think you’re doing?’

‘Keep ya shirt on, Mr. Meier,’ said the cheerful lad, ‘just getting it warmed up for ya.’

‘Yeah, well, thanks. Now get about your own business.’