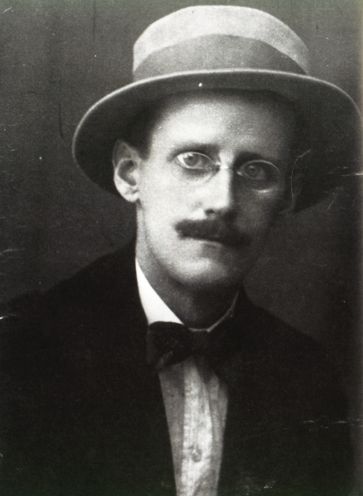

- Irish writer, James Joyce (1882-1941)

The first-person narrator, a boy, walks past the house of his dying priest night after night, wondering whether he is dead yet, but this night knows it to be true.

“Every night as I gazed up at the window I said softly to myself the word paralysis. It had always sounded strangely in my ears, like the word gnomon in the Euclid and the word simony in the Catechism.”

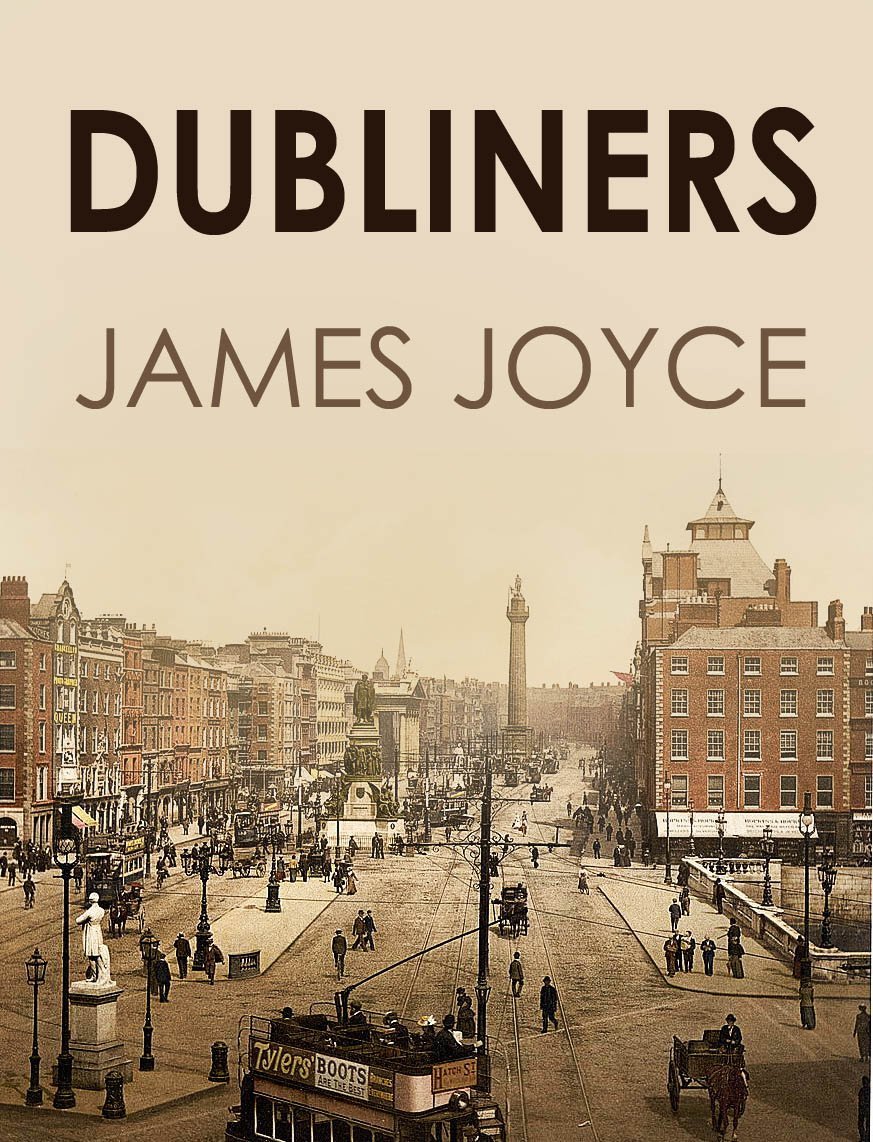

So begins the first story, The Sisters, in James Joyce’s collection Dubliners (1914) but in it is a clue to the theme of the book itself. Joyce wanted to write about the people of Dublin because to him it was the “city of paralysis” and the shadow of this word permeates the whole collection. For Joyce “paralysis” meant the inability to life meaningfully. Joyce spent most of his life on the continent, far away from Dublin, so strong was his belief that the city was tainted.

Here the “paralysis” is both literal, in the case of a dying priest after his third stroke, and moral: “simony” takes aim at the Catholic church’s corrupting stranglehold on Irish society; “gnomon” is somewhat different, being more about form than content (a gnomon is a parallelogram with a section removed, as well as the shadow-casting part of a sundial). The word is a cryptic warning to the reader that these stories contain many absences, not least traditional plot, character and scene-setting. These absences are part of what Joyce referred to as the style of “scrupulous meanness” with which he wrote Dubliners, meaning the frugality he applies to language, image and emotion.

Freytag’s pyramid, or dramatic arc or structure, suggests that a clear beginning consisting of a proper introduction of the setting and the characters, a middle discussing the conflict that would lead to a climax, and an end that ties the story together with a denouement are indispensable to any written work of fiction.

So was the literary thinking in 1914 – and in some circles it still is today. Joyce ignored it all, which may be why it took him 6 years to get this collection published.

In the story A Little Cloud, a shy and fragile clerk, known as Little Chandler, since “he gave one the idea of being a small man” meets in a bar, after 8 years, his friend Ignatius Gallaher, who once “known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press.” Little Chandler yearns of becoming a famous writer and dreams about the rave notices he would get for his work. He is delighted to see his old friend and Gallaher shouts him several whiskeys and regales the little man with innuendo and suggestions of his racy experiences in London and Paris: no married life for him. Of course, Little Chandler is late getting home to his young wife and child and had not brought the tea and sugar she had urged him not to forget. “She was in a bad humour and gave him short answers” and decides to go out and get the tea and sugar herself. “She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said: ‘Here. Don’t waken him’.” Little Gallaher cradles the child and stares at a photograph of his wife wearing an expensive blouse he had bought her. The image of his wife weaves no comparison to the “rich Jewesses” with “dark Oriental eyes” of Gallaher’s salacious plans and stories. Little Chandler feels nothing but entrapment, paralysis, in his mean little cottage with debt-laden furniture and no way of writing the book that “might open the way for him.” He reads some melancholy verse by Byron while nursing the child and wonders where he can find the time to write like that; he has so much to say. The baby wakes and cries and will not stop no matter how hard he tries to sooth him. Everything is useless. He is “a prisoner of life!” He loses his temper with the child and shouts at him which scares the infant and causes him to scream and “sob piteously”. His wife arrives and rescues the babe and glares at her useless husband and he listens to the child’s sobbing grow less and less in the arms of his loving mother. The story ends with Little Chandler just standing there as “tears of remorse started to his eyes.”

The reader is left with a feeling of pity and yearning for this little man who did the right thing, that every man should do, marry, start a family, and work to keep and protect them; while his friend did the other thing: travelled, wrote and became famous and whored around in London and Paris. This is the ending that Freytag’s pyramid espouses but it is a thought, not on the page but in the mind of the reader.

This was radical for 1914, when this collection first appeared. However, is it true today that more and more writers of fiction are leaving aspects of descriptive, consequential, and circumstantial narrative out of the text and up to the reader. This is so true that it is not the writer’s place any more to answer the question, “And what did you mean by writing that?” After a story is in print – or, for that matter any creative work that is finally in the public domain – the meaning of what the reader reads is all to do with the reader – it means what the reader thinks it means – and has nothing to do any more with the writer and what was meant by the writer in the first place.

Although Dubliners is considered one of the greatest short story collections ever written, it is Anton Chekhov, the Russian playwright, who is generally considered the father of the modern short story. “The revolution that Chekhov set in train – and which reverberates still today – was not to abandon plot” – or Freyberg’s Pyramid – “but to make the plot of his stories like the plot of our lives: random, mysterious, run-of-the-mill, abrupt, chaotic, fiercely cruel, meaningless”. Chekhov’s short stories had been available in English since 1903, but Joyce didn’t get Dubliners published until 1914. He claims not to have read them. Many critics think this a little implausible since Dubliners seems to owe a lot to the work of the Russian. However, Joyce finished the collection by 1907, and with Chekhov’s work having been available in English only for a few years when Joyce was working as a teacher in Europe, it is entirely possible that he did not read it. Although William Boyd, American novelist and short story writer asserts that Chekhov liberated Joyce’s imagination as much as Joyce liberated writers that followed and “that the Chekhovian point of view is to look at life in all its banality and all its tragic comedy and refuse to make a judgment”. The Joycean view seems to look at life from the inside of his characters: to chart his country’s “moral history” in Dublin; and he does this by turning the plot inwards. It’s the landscape of dreams, desires, hopes and disappointments that bind the 15 stories together into a whole, which in itself is unique, creating a form of a novel in fifteen disparate but morally interconnected chapters: the early stories are from childhood, the centre charts the middle years, and the final devastating story, The Dead, his masterpiece, culminates in a mature realisation of man’s insignificance in the universe. In fact, the first image of the first story: a boy looking up at a window behind which lies a dead man, is reflected in the last image of the last story where a man looks out of a window contemplating all the dead that have gone before him and which one day he will join. Images like bookends.

Joyce’s narrator varies from story to story: first person in the first, but usually in the third-person but not of the omniscient kind:

“…as he set himself to fan the fire again, his crouching shadow ascended the opposite wall and his face slowly reemerged into the light. It was an old man’s face, very bony and hairy.” (Ivy Day in the Committee Room). The narrator doesn’t know the face until it is seen as everyone else sees it, including the reader. It’s like the narrator and the reader see and know everything at the same time; as if you and he are watching the scene together.

It is the final story, The Dead, that marks Joyce a masterful writer and it is easy to argue that it is the best short story ever written. It is the quintessential modern story although it’s structure is almost classic. It opens with a scene featuring minor players in the story; a device used by Shakespeare in the opening scenes of many of his plays: it’s a way to introduce the scene and action before the principle players emerge, creating setting, background, and expectation. The bulk of the story is the colouring of the situation: the interconnecting relationships, the characters, the party as life’s metaphor, building tension and expectation, preparing the reader for what will happen.

Lily the house maid is “run off her feet” tending to guests as they arrive for the annual dance party given by the aging Misses Morkan, Kate and Julia, and their niece Mary-Jane, a music teacher to some of the “better-class families on the Kingstown and Dalkey line.” All eyes and ears are attuned to the arrival of Gabriel Conroy, the old ladies’ nephew, and his wife, Gretta, but they are also worried that the local drunk, the course-featured Freddie Mullins, might make a too-soon appearance and spoil the party. All arrive as expected and the party is in full swing; shoes shuffle and skirts swish and sway to the dance music on the polished floor of the upstairs parlor under the chandelier and a piano recital is given by Mary-Jane and songs are sung by the talented tenor, Mr Bartell D’Arcy. The strata of Dublin society are represented: the proud and successful Gabriel and his unhappy wife, Gretta; the Morkans drenched in their good-natured, middle-class hospitality cocooned in their well-established morality; and the likes of Freddie Mullins who prizes a drink over employment, filial duty, and nationalistic pride.

And then there are the galoshes. Gabriel wears them and urges his wife to, but she refuses. They are a symbol of modernity, recently arrived from London and “Gabriel says everyone wears them on the continent”. They are a sign of progress but, of course, the locals don’t wear them, much to Gabriel’s disappointment, thinking that he may have been able to bring the modern world into the lives of his community and family; Aunt Julia isn’t even sure what they are; Gretta thinks they’re funny and “says the word reminds her of the Christy Minstrels”. The social boundaries are clearly drawn.

On the dance floor, Gabriel, preoccupied with his forthcoming speech and worrying that his planed quotes from Browning “would be above the heads of his listeners”, is half-jokingly harassed by his dance partner, Miss Ivors, who “has a crow to pluck” with him. She chastises him for writing book-reviews for an English newspaper; refusing to holiday in his “own land” among his “own people” and to speak his “own language” and therefore labels him a ‘West Briton”.

Gabriel is a dignified man. He is angered by Miss Ivor’s assertions regardless of her light-hearted tone; considers Dublin, like Joyce, a back-water of pseudo-happy and ignorant people; looks to England and Europe for artistic, fruitful, and intellectual sustenance; but, despite all this, tonight he is excited by the idea of Gretta and he spending the night, without the children, in a local hotel. Their marriage has soured over the past few years into something that he sees as all too common in this society. He is hoping for, maybe even lustful, but at least an intimate night alone with his wife.

After all the singing, dancing, and a minor ruffle between the Catholics and “the other persuasion”, the goose is carved at the head of a fine, happy, and plentiful supper table. Gabriel’s speech is a great success. The champagne flows freely. The annual party is drawing to a close and Gabriel while putting on his coat asks after his wife. He finds her standing high on the landing in the semi-darkness gazing at nothing in particular but seemingly listening to something. There is a plaintive singing voice “in the old Irish tonality” and distant chords on a piano that seemed to render his wife transfixed. This is the peak of the drama. What is happening to Gretta, what is going on in her mind, will bring down the story’s protagonist. But Joyce stretches the tension. There is the walk with others into the city, then to the hotel, then to their room, and their preparation for the night. Here, he, all expectant and eager, is willed finally to ask why she is so melancholy. Her reply, his reaction, and the devastating realisation because of it, ends the story.

What begins as a classically structured tale of Dublin life, full of Chekhovian realism bolstered by detail, humour, character, emotional connections, and social hierarchy, the epitome of life itself, ends as a modern fable, not based on action, but internal thought. And like all good writers, Joyce ends with an image: a disappointed and humbled man gazing through a window on to a darkened city as snow gently begins to fall all over Ireland.

“His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

-oOo-

The works of James Joyce, Dubliners, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses, and Finnegan’s Wake, are out of copyright and can be downloaded, via various formats, for free here.